Christmas Message 1999

1968-12-24 (Apollo-8)

In 1977, the United States launched two robotic space probes as part of NASA's Voyager program. By 1989, both had crossed the orbit of Neptune and were well on their way to leaving our solar system.

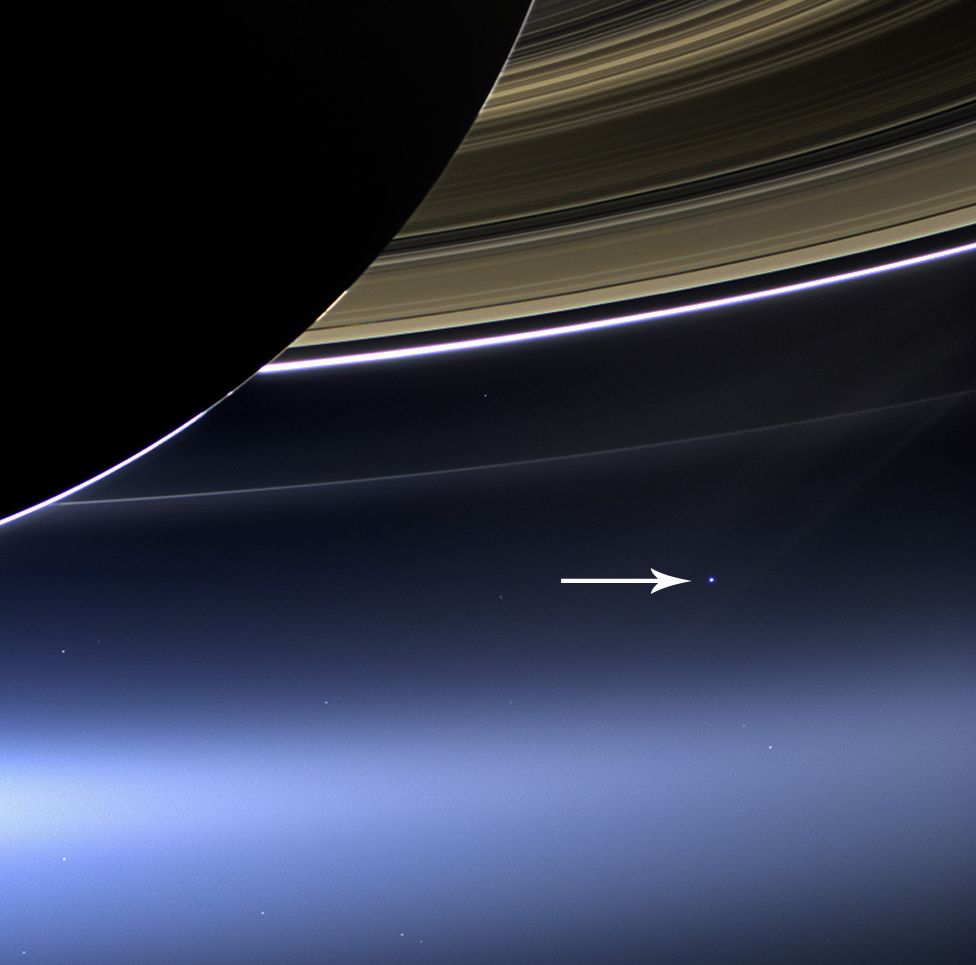

At that time, Carl Sagan remembered how the famous photograph "Earthrise above the Moon" (taken Christmas eve 1968, by the crew of Apollo-8) had forced humanity to step back and see Earth as just another part of the universe.

Notice that Earth's atmosphere appears incredibly thin (relatively speaking, "no thicker than the skin of an apple" or "the shellac coating on a schoolroom globe"). Our precious planet appears fragile while unique. No national borders can be seen, not even the Great Wall of China. All of humanity occupies a common biosphere. We are all in this world together. Some have labeled this cognitive shift the Overview Effect.

comment: The zeitgeist of those years caused the American congress under Republican president Richard Nixon to create the EPA (United States Environmental Protection Agency) and NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) in 1970. It seems that Rachel Carson (author of the 1962 book: Silent Spring) had been right all along.

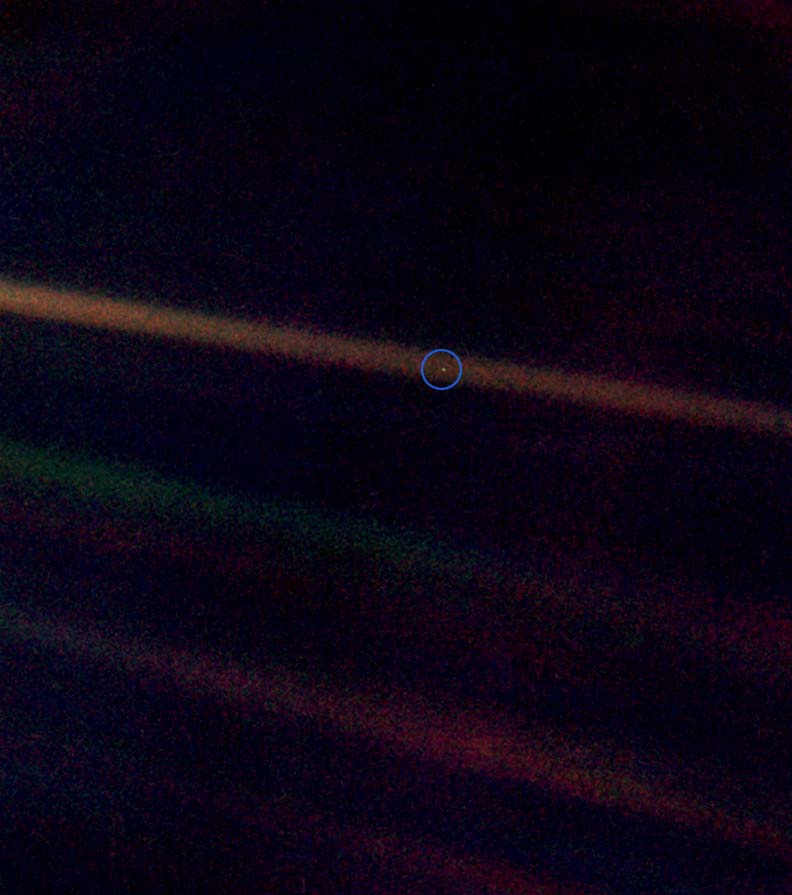

"Voyager 1" view of Earth from 6.4 billion km

In the spirit of the previous cognitive shift years ago, Sagan convinced NASA/JPL to swing Voyager 1 cameras around to take this 1990 goodbye picture of Earth at a distance of 6.4 billion km (4 billion miles).

Sagan Speaks:

We succeeded in taking that picture from just past the orbit of Neptune, and if you look at it, you see a dot. (the blue circle was added by an artist; the beautiful colored streaks are chromatic aberrations inside the camera)

Look again at that dot. That's here. That's home. That's us. On it everyone you love, everyone you know, everyone you ever heard of, every human being whoever was, lived out their lives. The aggregate of our joy and suffering, thousands of confident religions, ideologies, and economic doctrines, every hunter and forager, every hero and coward, every creator and destroyer of civilization, every king and peasant, every young couple in love, every mother and father, hopeful child, inventor and explorer, every teacher of morals, every corrupt politician, every "superstar," every "supreme leader," every saint and sinner in the history of our species lived there-on a mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam.

The Earth is a very small stage in a vast cosmic arena. Think of the endless cruelties visited by the inhabitants of one corner of this pixel on the scarcely distinguishable inhabitants of some other corner, how frequent their misunderstandings, how eager they are to kill one another, how fervent their hatreds. Think of the rivers of blood spilled by all those generals and emperors so that, in glory and triumph, they could become the momentary masters of a fraction of a dot.

Our posturings, our imagined self-importance, the delusion that we have some privileged position in the Universe, are challenged by this point of pale light. Our planet is a lonely speck in the great enveloping cosmic dark. In our obscurity, in all this vastness, there is no hint that help will come from elsewhere to save us from ourselves.

The Earth is the only world known so far to harbor life. There is nowhere else, at least in the near future, to which our species could migrate. Visit, yes. Settle, not yet. Like it or not, for the moment the Earth is where we make our stand.

It has been said that astronomy is a humbling and character-building experience. There is perhaps no better demonstration of the folly of human conceits than this distant image of our tiny world. To me, it underscores our responsibility to deal more kindly with one another, and to preserve and cherish the pale blue dot, the only home we've ever known.

speech at Cornell University

October 13, 1994

(Earth is a) Pale Blue Dot

Excerpt from the book: "Pale Blue Dot" Chapter 1: You Are Here

Republished: 2020-02-14

(NASA/JPL employed modern software tools to reprocess the original data)

Obediently, it turned its cameras back toward the now-distant planets. Slewing its scan platform from one spot in the sky to another, it snapped 60 pictures and stored them in digital form on its tape recorder. Then, slowly, in March, April, and May, it radioed the data back to Earth. Each image was composed of 640,000 individual picture elements (“pixels”), like the dots in a newspaper wirephoto or a pointillist painting. The spacecraft was 3.7 billion miles away from Earth, so far away that it took each pixel 5½ hours, traveling at the speed of light, to reach us. The pictures might have been returned earlier, but the big radio telescopes in California, Spain, and Australia that receive these whispers from the edge of the Solar System had responsibilities to other ships that ply the sea of space—among them, Magellan, bound for Venus, and Galileo on its tortuous passage to Jupiter.

Voyager 1 was so high above the ecliptic plane because, in 1981, it had made a close pass by Titan, the giant moon of Saturn. Its sister ship, Voyager 2, was dispatched on a different trajectory, within the ecliptic plane, and so she was able to perform her celebrated explorations of Uranus and Neptune. The two Voyager robots have explored four planets and nearly sixty moons. They are triumphs of human engineering and one of the glories of the American space program. They will be in the history books when much else about our time is forgotten.

The Voyagers were guaranteed to work only until the Saturn encounter. I thought it might be a good idea, just after Saturn, to have them take one last glance homeward. From Saturn, I knew, the Earth would appear too small for Voyager to make out any detail. Our planet would be just a point of light, a lonely pixel, hardly distinguishable from the many other points of light Voyager could see, nearby planets and far-off suns. But precisely because of the obscurity of our world thus revealed, such a picture might be worth having.

Mariners had painstakingly mapped the coastlines of the continents. Geographers had translated these findings into charts and globes. Photographs of tiny patches of the Earth had been obtained first by balloons and aircraft, then by rockets in brief ballistic flight, and at last by orbiting spacecraft—giving a perspective like the one you achieve by positioning your eyeball about an inch above a large globe. While almost everyone is taught that the Earth is a sphere with all of us somehow glued to it by gravity, the reality of our circumstance did not really begin to sink in until the famous frame-filling Apollo photograph of the whole Earth—the one taken by the Apollo 17 astronauts on the last journey of humans to the Moon.

It has become a kind of icon of our age. There’s Antarctica at what Americans and Europeans so readily regard as the bottom, and then all of Africa stretching up above it: You can see Ethiopia, Tanzania, and Kenya, where the earliest humans lived. At top right are Saudi Arabia and what Europeans call the Near East. Just barely peeking out at the top is the Mediterranean Sea, around which so much of our global civilization emerged. You can make out the blue of the ocean, the yellow-red of the Sahara and the Arabian desert, the brown-green of forest and grassland.

And yet there is no sign of humans in this picture, not our reworking of the Earth’s surface, not our machines, not ourselves: We are too small and our statecraft is too feeble to be seen by a spacecraft between the Earth and the Moon. From this vantage point, our obsession with nationalism is nowhere in evidence. The Apollo pictures of the whole Earth conveyed to multitudes something well known to astronomers: On the scale of worlds—to say nothing of stars or galaxies—humans are inconsequential, a thin film of life on an obscure and solitary lump of rock and metal.

It seemed to me that another picture of the Earth, this one taken from a hundred thousand times farther away, might help in the continuing process of revealing to ourselves our true circumstance and condition. It had been well understood by the scientists and philosophers of classical antiquity that the Earth was a mere point in a vast encompassing Cosmos, but no one had ever seen it as such. Here was our first chance (and perhaps also our last for decades to come).

Many in NASA’s Voyager Project were supportive. But from the outer Solar System the Earth lies very near the Sun, like a moth enthralled around a flame. Did we want to aim the camera so close to the Sun as to risk burning out the spacecraft’s vidicon system? Wouldn’t it be better to delay until all the scientific images—from Uranus and Neptune, if the spacecraft lasted that long—were taken?

And so we waited, and a good thing too—from 1981 at Saturn, to 1986 at Uranus, to 1989, when both spacecraft had passed the orbits of Neptune and Pluto. At last, the time came. But there were a few instrumental calibrations that needed to be done first, and we waited a little longer. Although the spacecraft were in the right spots, the instruments were still working beautifully, and there were no other pictures to take, a few project personnel opposed it. It wasn’t science, they said. Then we discovered that the technicians who devise and transmit the radio commands to Voyager were, in a cash-strapped NASA, to be laid off immediately or transferred to other jobs. If the picture were to be taken, it had to be done right then. At the last minute—actually, in the midst of the Voyager 2 encounter with Neptune—the then NASA Administrator, Rear Admiral Richard Truly, stepped in and made sure that these images were obtained. The space scientists Candy Hansen of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) and Carolyn Porco of the University of Arizona designed the command sequence and calculated the camera exposure times.

So here they are—a mosaic of squares laid down on top of the planets and a background smattering of more distant stars. We were able to photograph not only the Earth, but also five other planets of the Sun’s known nine. Mercury, the innermost, was lost in the glare of the Sun, and Mars and Pluto were too small, too dimly lit, and/or too far away. Uranus and Neptune are so dim that recording their presence required long exposures; accordingly, their images were smeared because of spacecraft motion. This is how the planets would look to an alien spaceship approaching the Solar System after a long interstellar voyage.

From this distance the planets seem only points of light, smeared or unsmeared—even through the high-resolution telescope aboard Voyager. They are like the planets seen with the naked eye from the surface of the Earth—luminous dots, brighter than most of the stars. Over a period of months the Earth, like the other planets, would seem to move among the stars. You cannot tell merely by looking at one of these dots what it’s like, what’s on it, what its past has been, and whether, in this particular epoch, anyone lives there.

Because of the reflection of sunlight off the spacecraft, the Earth seems to be sitting in a beam of light, as if there were some special significance to this small world. But it’s just an accident of geometry and optics. The Sun emits its radiation equitably in all directions. Had the picture been taken a little earlier or a little later, there would have been no sunbeam highlighting the Earth.

And why that cerulean color? The blue comes partly from the sea, partly from the sky. While water in a glass is transparent, it absorbs slightly more red light than blue. If you have tens of meters of the stuff or more, the red light is absorbed out and what gets reflected back to space is mainly blue. In the same way, a short line of sight through air seems perfectly transparent. Nevertheless, something Leonardo da Vinci excelled at portraying, the more distant the object, the bluer it seems. Why? Because the air scatters blue light around much better than it does red. So, the bluish cast of this dot comes from its thick but transparent atmosphere and its deep oceans of liquid water. And the white? The Earth on an average day is about half covered with white water clouds.

We can explain the wan blueness of this little world because we know it well. Whether an alien scientist newly arrived at the outskirts of our solar system could reliably deduce oceans and clouds and a thickish atmosphere is less certain. Neptune, for instance, is blue, but chiefly for different reasons. From this distant vantage point, the Earth might not seem of any particular interest.

But for us, it’s different. Look again at that dot. That’s here. That’s home. That’s us. On it everyone you love, everyone you know, everyone you ever heard of, every human being whoever was, lived out their lives. The aggregate of our joy and suffering, thousands of confident religions, ideologies, and economic doctrines, every hunter and forager, every hero and coward, every creator and destroyer of civilization, every king and peasant, every young couple in love, every mother and father, hopeful child, inventor and explorer, every teacher of morals, every corrupt politician, every “superstar,” every “supreme leader,” every saint and sinner in the history of our species lived there—on a mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam.

The Earth is a very small stage in a vast cosmic arena. Think of the rivers of blood spilled by all those generals and emperors so that, in glory and triumph, they could become the momentary masters of a fraction of a dot. Think of the endless cruelties visited by the inhabitants of one corner of this pixel on the scarcely distinguishable inhabitants of some other corner, how frequent their misunderstandings, how eager they are to kill one another, how fervent their hatreds.

Our posturings, our imagined self-importance, the delusion that we have some privileged position in the Universe, are challenged by this point of pale light. Our planet is a lonely speck in the great enveloping cosmic dark. In our obscurity, in all this vastness, there is no hint that help will come from elsewhere to save us from ourselves.

The Earth is the only world known so far to harbor life. There is nowhere else, at least in the near future, to which our species could migrate. Visit, yes. Settle, not yet. Like it or not, for the moment the Earth is where we make our stand.

It has been said that astronomy is a humbling and character-building experience. There is perhaps no better demonstration of the folly of human conceits than this distant image of our tiny world. To me, it underscores our responsibility to deal more kindly with one another, and to preserve and cherish the pale blue dot, the only home we’ve ever known.

"Because of the reflection of sunlight off the spacecraft, the Earth seems to be sitting in a beam of light, as if there were some special significance to this small world. But it's just an accident of geometry and optics. The Sun emits its radiation equitably in all directions. Had the photograph been taken a little earlier, or a little later, there would have been no sunbeam highlighting the Earth."

Science, Technology and Engineering

Voyager Missions Exit the Solar System

By scientific definition, the solar system only extends as far as our Sun's heliosphere. The boundary is known as the heliopause and is past the orbit of Pluto (properly reclassified from a planet to a Kuiper Belt object in 2006).

- Voyager 1 exits the solar system (2013-09-12)

- Voyager 2 exits the solar system (2018-12-10)

- NASA Confirms Voyager 2 Has Left the Solar System (2019-11-05)

- Voyager 2’s Notes from Interstellar Space | SciShow News (2019-11-08)

NASA fires Voyager 1 engines for the first time in 37 years

(via New Scientist magazine)

date: 2017-12-05

It’s alive! By firing a set of thrusters that have been gathering dust for more than 3 decades, NASA has extended the lifetime of the Voyager 1 mission by a few years.

The interstellar probe is 13 billion miles away, moving at a speed of over 17 kilometers per second, but it still manages to send messages back to Earth. In order to do that, it needs to keep its antenna pointed towards us.

After 40 years in space, the thrusters that orient the spacecraft and keep its antenna aiming in the right direction have started to break down.

NASA engineers decided to try firing the craft’s backup thrusters, which have been dormant for 37 years. Then, they had to wait 19 hours and 35 minutes to get a signal from Voyager 1 at the edge of our solar system. The long shot worked, and NASA scientists plan to fully switch over to the backup thrusters in 2020.

The Voyager flight team dug up old records and studied the original software before tackling the test. As each milestone in the test was achieved, the excitement level grew, said propulsion engineer Todd Barber. “The mood was one of relief, joy and incredulity after witnessing these well-rested thrusters pick up the baton as if no time had passed at all,” he said in a statement.

By switching out the thrusters, Voyager 1 may be able to keep sending us messages for a little while longer, until around 2025. Launched in 1977, Voyager 1 is the only spacecraft traveling through interstellar space, the region beyond our solar system. Voyager 2 is close on its heels, nearly 11 billion miles from Earth. The thruster test worked so well that NASA expects to try it on Voyager 2 in the future.

Read more at New Scientist magazine:More Links

- Where are they now?

- NASA Just Fired Voyager 1’s Thrusters For the First Time in 37 Years (2017-12-04)

The Human Condition

Seasonal Song: "I Believe in Father Christmas"

Greg Lake (member of Emerson Lake and Palmer) passed away on December 7, 2016."I Believe in Father Christmas"

Here are the lyrics of his song: I Believe in Father Christmas

They said there'll be snow at Christmas

They said there'll be peace on earth

But instead it just kept on raining

A veil of tears for the virgin's birth

I remember one Christmas morning

A winters light and a distant choir

And the peal of a bell and that Christmas tree smell

And their eyes full of tinsel and fire

They sold me a dream of Christmas

They sold me a silent night

And they told me a fairy story

'till I believed in the Israelite

And I believed in father Christmas

And I looked to the sky with excited eyes

'till I woke with a yawn in the first light of dawn

And I saw him and through his disguise

I wish you a hopeful Christmas

I wish you a brave new year

All anguish pain and sadness

Leave your heart and let your road be clear

They said there'll be snow at Christmas

They said there'll be peace on earth

Hallelujah noel, be it heaven or hell

The Christmas we get, we deserve

Comments about the last two lines

When I was growing up in the 1950s, I was taught the Christmas greeting "peace on Earth and good will to all men". In my adult years I learned that this was a poor translation of "peace on Earth to men of good will". This means that this blessing "is conditional" and based upon the behavior of the recipient (are you a person of good will? what about your culture, country or religion?)

As the song says, we will get the Christmas we deserve based upon our personal and collective actions. Individually we must care for others as well as the whole Earth. Collectively we must vote for peacemakers while advocating for environmentalism as well as non-violence. What would Jesus say about American drone strikes in the middle east, or NATO countries like America, Britain, France and Canada selling arms to foreign countries to support wars elsewhere? What would Jesus say about the USA supporting the Israeli extermination of people in Gaza?

comments: with trigger events like the Siege of Waco, Texas (which spawned citizen militias), or the first mass school shooting in Columbine, Colorado (which spawned many more), it seems to me that the USA has not received the provisional season's blessing in more than 30 years. Karma? Perhaps.

On 2023-11-07, Hamas, an Islamic terrorist group, killed 1,400 Israeli citizens which was later revised to 1,200 (although most people continue to quote the higher number). As I write this on 2023-12-22, Israel's military response has killed more than 20,000 Palestinians, the majority who are women and children. Update: A year later (2024-12-20) this number now stands are 41,000. This Old Testament philosophy was something Jesus spoke against when he admonished Jews to move from "obeying the letter of Jewish law (Torah)" to "the spirit of the law (doing good works on the Sabbath are not illegal)", and he was crucified for it.

“Now go and attack the Amalekites and completely destroy everything they have. Do not spare them. Kill men and women, infants and nursing babies, oxen and sheep, camels and donkeys.” (1 Samuel 15:3)

So why does the United States of America, a self-described Christian nation, continue to supply military hardware to Israel which enables Israel to carry out Old Testament revenge? Do Americans not know that Christianity is a non-violent philosophy of the New Testament? Do they not know that the Old Testament was done away with by Jesus and his followers?

Christmas and American Extreme Capitalism

Every December, many people in the western world will read or watch the Charles Dickens story A Christmas Carol (1843) then will kick back and congratulate themselves for not being anything at all like Ebenezer Scrooge. And yet, the actions of extreme capitalists are the moral equivalent of Scrooge with one exception: unlike Scrooge, they will never realize the error of their ways. For example, in order to maximize their profits, activist hedge funds demand that large companies move work to other locations where wages, taxes, and regulations are the lowest (IMHO, this is the true cause of the homelessness crisis). If they had their way, businesses would not offer pensions, medical benefits or paid holidays "including Christmas". If they had their way, businesses would be money-generating machines with no employees. Tiny Tim is probably living somewhere in Indochina making iPhones for the North American marketplace.

Americans are always banging on about Adam Smith and "the invisible hand of the market" which is attributed to his second book The Wealth of Nations (1776), but Adam Smith (an economist was known as a moral philosopher in those days) wrote an earlier book titled The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759) which seems to conflict with portions of The Wealth of Nations. German scholars refer to this conflict as "Das Adam Smith Problem" while Americans simply ignore the first book.

The “Adam Smith Problem” is the name given to an argument that arose among German scholars during the second half of the nineteenth century concerning the compatibility of the conceptions of human nature advanced in, respectively, Adam Smith's Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759) and his Wealth of Nations (1776). During the twentieth century these arguments were forgotten but the problem lived on, the consensus now being that there is no such incompatibility, and therefore no problem. Rather than rehearse the arguments for and against compatibility and incompatibility, this paper returns to the German writers of the 1850s–1890s and demonstrates that their engagement in this argument represents the foundation of modern Smith scholarship. It is shown that the “problem” was not simply a mistake best forgotten, but the first sustained scholarly effort to understand the importance of Smith's work, an effort that lacked any parallel in English commentary of the time. By the 1890s British writers, overwhelmingly ignorant of German commentary, assumed that there was little more to be said about Smith's work. Belated international familiarity with this German “Problem” played a major role in transforming Smith from a simple partisan of free trade into a theorist of commercial society and human action.

Anyway, I always wonder what Adam Smith would say about hedge funds, especially around Christmas. Many American citizens find this next item hard to believe, but

capitalism comes in many flavors, and the American interpretation is the greediest. What is practiced in Europe is closer to what Adam Smith had in mind (capitalism

blended with socialism). What is practiced in China (state sponsored capitalism) is very different, and yet, Chinese citizens are required to pay income taxes in order to help defray the costs of their system. China collects corporate taxes as well. But here's the kicker: many pieces of

the Chinese financial system were copied from western governments after China paid to have more than 1.3 million students educated in America and Europe, then return home to advise the Chinese government. This is how Deng Xiaoping moved more that 350 million Chinese citizens from poverty into the middle class.

Update: by 2024 the total number exceeded 850 million (more than twice the current population of the USA).

Economics Today

- I recently changed my perspective on economics and Macroeconomics after watching this YouTube video from the London School of Economic where I learned that, in Macroeconomics, you need to replace "90% of the math" with "history". Why? Economics is all

about humanity (and the associated drive for progress)

ref1: "Too much Maths, too little History: The problem of Economics" https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6rXBBqMmIP8 - I recently attended a 24-lecture course by Edward F. Stuart, Ph.D. titled "Socialism vs. Capitalism" which is taught in an historical context.

IMHO this course is misnamed. It should have been called "Comparative Economics: Socialism vs. Capitalism"

ref2: https://www.thegreatcoursesplus.com ($20 per month or $45 per quarter) - For Profit: A History of Corporations (Michael Shermer and William Magnuson): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v23eFysjK2o

- Who Was Karl Marx? And Why Is Everyone Still Talking About Him? https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3imIf8NAcWQ

- Capitalism was not possible without the Protestant Reformation

- The demand-supply curve came from Alfred Marshall (not Adam Smith)

- The word "capitalism" first appeared in Karl Marx's book Das Kapital (probably to be used as a pejorative)

- Marx hated seeing people used as beasts-of-burden so advocated for "Universal, Free, and Compulsory Public Education (In The Communist Manifesto)", "elementary education for all children, and the elimination of child labor in factories", "Polytechnic Education", "Combination of Labor and Learning", "Education as a tool for liberation", "Lifelong Learning", forming "Trade Unions" to act as a body of “stake holders” which would stand as a counterbalance to “share holders”.

- At the end of his life, Marx said, "All I know is that I don't think I'm a Marxist!"

- According to John Maynard Keynes who unsuccessfully advised the politicians crafting the Treaty of Versailles, the "treaty's politicians" were ignorant of economics and Macroeconomics, so were unable to see that driving Germany into poverty would eventually affect the rest of Europe and the world. History informs that the recession in Europe was a factor in the American banking failures that followed the 1929 stock market crash (American banks had lent money to Germany after 1918 to help rebuild). We all now know that the recession in Germany contributed to the rise in German fascism, Adolph Hitler and the NAZI party. I wonder how much time, money and lives were wasted by the allies in WW2 to regain control of this situation.

1972 Paradigm Shift?

- In the Forward to his book: "The Collected Stories of Arthur C. Clarke" the author wrote "Science Fiction is something that could happen - but usually you wouldn't want it to. Fantasy is something that couldn't happen - though often you only wish that it could"

- I recently stumbled onto this (perhaps better) quote by Gary K. Wolfe: "Science Fiction takes place on a planet while Fantasy takes place in a world"

Thinking about that second definition for a moment, many believe that humanity was forever changed after collectively viewing the The Blue Marble photo published in 1972. It is one thing to know that we live on a planet, as people have done for more than 400 years, but seeing proof is something else. But this got me thinking about creation myths like the Judaeo-Christian story about "The Garden of Eden" (better translation: "The Garden East of Eden") which is quite possibly just a fantasy story from a bronze-age world. Time for humanity to move to science-based stories.