Hacker Perspective: Recommended Books (the human condition)

The Human Condition (biographies, economics, politics, etc.)

jump: biology (another page)

The Greatest Sentence Ever Written (2025) Walter Walter Isaacson

The Greatest Sentence Ever Written is the title of a book just published by author Walter Isaacson about the opening text of the American Declaration of Independence.

excerpt: "We hold these truths to be sacred..." Sacred? No. That doesn't sound right. But that is how Thomas Jefferson wrote it in his first draft.

Benjamin Franklin, who was on the five-person drafting committee with Jefferson, crossed out "sacred," using the heavy backlash marks he had used as as printer, and wrote

"self-evident". The declaration they were writing was intended to herald a new type of nation, one in which our rights are based on reason, not the dictates or dogma of

religion.

comment: This 80-page book is real treat and would make a nice Christmas addition to any family library. Probably due to the Pilgrims landing in

1620, many American citizens today think the USA was created as a Christian nation. This book corrects that error by demonstrating that the Declaration of

Independence was a creation of the Enlightenment and associated with Deism (see page 19)

1984 Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949) George Orwell

In 1984, London is a grim city in the totalitarian state of Oceania where Big Brother is always watching you and the Thought Police can practically read your mind. Winston Smith is a man in grave danger for the simple reason that his memory still functions. Drawn into a forbidden love affair, Winston finds the courage to join a secret revolutionary organization called The Brotherhood, dedicated to the destruction of the Party. Together with his beloved Julia, he hazards his life in a deadly match against the powers that be.

comments: I first encountered this book as a teenager, but that was ages ago. Recently, I decided to revisit the story by watching the film adaptation starring Richard Burton (as O'Brien) on Amazon Prime. It didn’t take long before frustration set in—many of the key Newspeak terms like INGSOC and ARTSEM weren’t explained at all. I kept pausing the movie to look things up on my phone, which eventually convinced me to buy and reread the book. The content is undeniably bleak, especially because echoes of Newspeak seem to permeate modern discourse. In my view, no government has ever truly heeded Orwell’s warnings. Interestingly, Orwell reportedly based the novel on life in London circa 1948—he simply flipped the last two digits to create the title. Did you know the U.S. rebranded its “Department of War” as the “Department of Defense” in 1949? That kind of linguistic shift feels straight out of Orwell’s playbook.

P.S. Trump recently reverted the name back to “Department of War.” I can’t help but wonder whether he—or anyone in his administration—is aware of the historical and literary implications. And why would someone demand a Nobel Peace Prize while actively funding military operations in Ukraine and Israel, and now seemingly provoking Venezuela?

update-1: I just discovered a book within this book titled "THE THEORY AND PRACTICE OF OLIGARCHICAL COLLECTIVISM" by "Emmanuel Goldstein" which

starts on page 177 (TPOC-ch1 , TPOC-ch3). This stuff is

much more scary than the original story because it sort of makes sense from a pretzel-logic point of view. On top of that, some of this stuff can be seen in modern USA.

Two examples of many:

- in this secondary text there is a mention of limiting education to the proles so they do not get too smart (which would upset the balance of the classes). Contrast this with Trump's plan to shut down the department of education.

- in this secondary text there is mention of party members needing to hold two opposing thoughts in one's head. The two examples are "2+2=4" and "2+2+5". For the purpose of building military weapons you must choose the former but for purposes of politics you must choose the latter AND believe it (known as doublethink). IMHO, Republican some diehards really believe climate change is a scam but to see Trump scold the world a few weeks ago at the UN, Trump's image could replace Big Brother's.

update-2: I was troubled by the fact that I missed the book-with-a-book during my first reading so many years ago. It turns out that this larger

material is only included in the hardcover versions of the book. It is heavily chopped down in the paperbacks. This means that it is hit or miss in the PDF copies.

Here's some additional material:

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Theory_and_Practice_of_Oligarchical_Collectivism

- https://www.cliffsnotes.com/literature/n/1984/summary-and-analysis/part-2-chapters-910

Breakneck: China's Quest to Engineer the Future (2025) Dan Wang

China - USA: Starting in 2017, the first Trump administration explicitly signaled—through words and actions—that the United States was entering a new Cold War but his time with China. Having experienced the American-instigated Cold War with Russia, I found this announcement concerning. Since then, I've been seeking insights to better understand the evolving situation and hopefully reduce tensions. That clarity came for me on September 28, 2025, while listening to the CBC's Front Burner podcast episode titled "The secret to China’s dominance". The episode featured an interview with Dan Wang, author of the book "Breakneck: China's Quest to Engineer the Future".Dan Wang, a tech analyst and research fellow at Stanford University's Hoover History Lab, is among the top China experts today. In Breakneck, he argues that China's rise in the 21st century stems largely from its identity as an "engineering state," whereas the U.S. is characterized as a more "lawyerly" society that sometimes hampers its own progress. The discussion delves into what this means, its broader implications, and whether the U.S. has any realistic chance to close the gap.

- https://www.cbc.ca/listen/cbc-podcasts/209-front-burner/episode/16171904-the-secret-to-chinas-dominance (28:26)

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZNK3vNg13XA (1:03:18)

quote: China didn't steal American jobs. American manufacturers exported American jobs to China in order to increase investor profit - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VaNy4J4cju8 (51:21)

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QP54j_r0IuQ (57:53)

additionally:

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UqBa0hBAQBA (1:05:45 | Why Trump Could Lose His Trade War With China | Ezra Klein interview with Thomas Friedman) quote: "Hire Clowns, expect a circus"

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qb644F-iE_s (2:27:29 | Why China's manufacturing economy is dominating | Dwarkesh Patel interview with Arthur Kroeber)

Understanding Capitalism (2024) Richard D. Wolff

The author begins with these three production abstractions...| Name/Label | actor -1 | actor-2 | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Slavery | master | slave | |

| Feudalism | Lord | Serf | The lords have all of the wealth and land, so offer military protection for serfs living nearby |

| Capitalism | Employer Lender |

Employee Borrower |

spreads from England after the decline of Feudalism |

| Capitalism2 | adds: hedge funds, activist investors |

this is my ad-hoc extension |

- One production system does not need to replace another. They can blend together

- The USA was late to slavery but tried to blend it with capitalism

- Feudalism is usually associated with Castles in Europe which were never seen in the USA. But America's "military industrial complex" linked to NATO makes me wonder if this is a "new feudalism" (just the military protection piece) linked to capitalism.

- It appears to me that union activity pushes employees in a direction "away from serfdom".

- When Ronald Reagan fired the air traffic controllers in 1981, he was pushing employees a direction "toward serfdom"

- In the days of Feudalism, the very rich could afford to build, and live in, castles. Today, the very rich are so wealthy that they can afford to build and operate their own rocket companies (something only previously possible by defense contractors operating from government contracts)

- If money is the proverbial lubricant responsible for greasing the machine we call the economy, then concentrating more wealth into the hands of the super wealthy will cause the machine to seize. At that point we will all be effectively living in a feudal state.

The Big Myth (2023) Naomi Oreskes

subtitled: How American Business Taught Us to Loathe Government and Love the Free Market

In the early 20th century, business elites, trade associations, wealthy powerbrokers, and media allies set out to build a new American orthodoxy: down with “big

government” and up with unfettered markets. With startling archival evidence, Oreskes and Conway document campaigns to rewrite textbooks, combat unions, and defend child

labor. They detail the ploys that turned hardline economists Friedrich von Hayek and Milton Friedman into household names; recount the libertarian roots of the Little

House on the Prairie books; and tune into the General Electric-sponsored TV show that beamed free-market doctrine to millions and launched Ronald Reagan's political

career.

By the 1970s, this propaganda was succeeding. Free market ideology would define the next half-century across Republican and Democratic administrations, giving us a

housing crisis, the opioid scourge, climate destruction, and a baleful response to the Covid-19 pandemic. Only by understanding this history can we imagine a future where

markets will serve, not stifle, democracy.

From Anti-Government to Anti-Science: Why Conservatives Have Turned Against Science

article: https://direct.mit.edu/daed/article/151/4/98/113706/From-Anti-Government-to-Anti-Science-Why abstract: In this essay, we argue that conservative hostility toward science is rooted in conservative hostility toward government regulation of the marketplace,

which has morphed in recent decades into conservative hostility to government, tout court. This distrust was cultivated by conservative business leaders

for nearly a century, but took strong hold during the Reagan administration, largely in response to scientific evidence of environmental crises that invited governmental

response. Thus, science (particularly environmental and public health science) became the target of conservative anti-regulatory attitudes. We argue that contemporary

distrust of science is mostly collateral damage, a spillover from carefully orchestrated conservative distrust of government.

comments:

- A better title would have been "how American big business hijacked Adam Smith's capitalism"

- Watch this podcast: Do Markets Need to be Regulated?

- Read this book: The Big Myth: How American Business Taught Us to Loathe Government and Love the Free Market

- related: watch this TVO interview with the author of the 2023 book Adam Smith's America

For Profit: A History of Corporations (2022) William Magnuson

From legacy manufacturers to emerging tech giants, corporations wield significant power over our lives, our economy, and our politics. Some celebrate them as engines of

progress and prosperity. Others argue that they recklessly pursue profit at the expense of us all.

In For Profit, law professor William Magnuson reveals that both visions contain an element of truth. The story of the corporation is a human story, about a diverse group

of merchants, bankers, and investors that have over time come to shape the landscape of our modern economy. Its central characters include both the brave, powerful,

and ingenious and the conniving, fraudulent, and vicious. At times, these characters have been one and the same.

Yet as Magnuson shows, while corporations haven’t always behaved admirably, their purpose is a noble one. From their beginnings in the Roman Republic, corporations have

been designed to promote the common good. By recapturing this spirit of civic virtue, For Profit argues, corporations can help craft a society in which all of us—not just

shareholders—benefit from the profits of enterprise.

Becoming Superman (2019) J. Micheal Straczynski

A Hugo Award Nominee!Joe's early life nearly defies belief. Raised by damaged adults—a con-man grandfather and a manipulative grandmother, a violent, drunken father and a mother who was repeatedly institutionalized—Joe grew up in abject poverty, living in slums and projects when not on the road, crisscrossing the country in his father’s desperate attempts to escape the consequences of his past.

To survive his abusive environment Joe found refuge in his beloved comics and his dreams, immersing himself in imaginary worlds populated by superheroes whose amazing powers allowed them to overcome any adversity. The deeper he read, the more he came to realize that he, too, had a superpower: the ability to tell stories and make everything come out the way he wanted it. But even as he found success, he could not escape a dark and shocking secret that hung over his family’s past, a violent truth that he uncovered over the course of decades involving mass murder.

Straczynski’s personal history has always been shrouded in mystery. Becoming Superman lays bare the facts of his life: a story of creation and darkness, hope and success, a larger-than-life villain and a little boy who became the hero of his own life. It is also a compelling behind-the-scenes look at some of the most successful TV series and movies recognized around the world.

Life is Simple (2021) Johnjoe McFadden

subtitled: How Occam's Razor Set Science Free and Shapes the Universe

highly recommended for all citizensCenturies ago, the principle of Ockham’s razor changed our world by showing simpler answers to be preferable and more often true. In Life Is Simple, scientist Johnjoe McFadden traces centuries of discoveries, taking us from a geocentric cosmos to quantum mechanics and DNA, arguing that simplicity has revealed profound answers to the greatest mysteries. This is no coincidence. From the laws that keep a ball in motion to those that govern evolution, simplicity, he claims, has shaped the universe itself. And in McFadden’s view, life could only have emerged by embracing maximal simplicity, making the fundamental law of the universe a cosmic form of natural selection that favors survival of the simplest. Recasting both the history of science and our universe’s origins, McFadden transforms our understanding of ourselves and our world.

comment:

- Not sure if this book should here or in the science section

- 300 years before Galileo's arrest by the Catholic church, William of Occam was arrested and charged with heresy for questioning the Catholic church's pronouncements on science. Perhaps the best example of Occam's Razor is when William cut science away from theology (or was it the other way around?)

- chapters 16-19 (quantum mechanics and cosmology) were an unexpected pleasure containing stuff not so simple

- chapter 19 contains some interesting cosmological speculation from Lee Smolin of Canada's Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics.

- make sure you read the epilogue

The Frontiers of Knowledge (2021) A. C. Grayling

subtitled: What we know about science, history and the mind

comment: Not sure if this book should here or in the science section

In very recent times humanity has learnt a vast amount about the universe, the past, and itself. But through our remarkable successes in acquiring knowledge we have

learned how much we have yet to learn: the science we have, for example, addresses just 5 per cent of the universe; pre-history is still being revealed, with thousands of

historical sites yet to be explored; and the new neurosciences of mind and brain are just beginning.

What do we know, and how do we know it? What do we now know that we don't know? And what have we learnt about the obstacles to knowing more? In a time of deepening

battles over what knowledge and truth mean, these questions matter more than ever. Bestselling polymath and philosopher A. C. Grayling seeks to answer them in three

crucial areas at the frontiers of knowledge: science, history and psychology. A remarkable history of science, life on earth, and the human mind itself, this is a

compelling and fascinating tour de force, written with verve, clarity and remarkable breadth of knowledge.

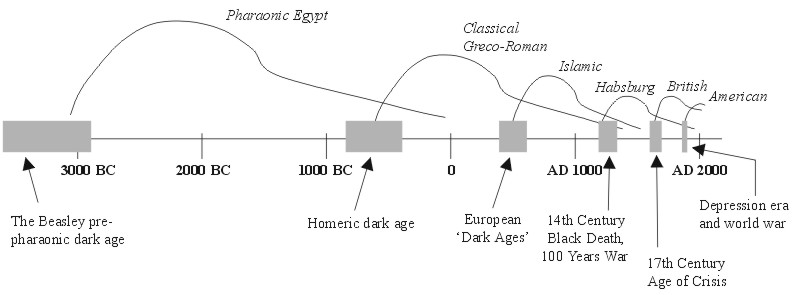

To Govern the Globe (2021) Alfred W McCoy

subtitled: World Orders & Catastrophic Change

In a tempestuous narrative that sweeps across five continents and seven centuries, this book explains how a succession of catastrophes—from the devastating Black Death

of 1350 through the coming climate crisis of 2050—has produced a relentless succession of rising empires and fading world orders. During the long centuries of Iberian and

British imperial rule, the quest for new forms of energy led to the development of the colonial sugar plantation as a uniquely profitable kind of commerce. In a time when

issues of race and social justice have arisen with pressing urgency, the book explains how the plantation’s extraordinary profitability relied on a production system that

literally worked the slaves to death, creating an insatiable appetite for new captives that made the African slave trade a central feature of modern capitalism for over

four centuries. After surveying past centuries roiled by imperial wars, national revolutions, and the struggle for human rights, the closing chapters use those hard-won

insights to peer through the present and into the future. By rendering often-opaque environmental science in lucid prose, the book explains how climate change and

changing world orders will shape the life opportunities for younger generations, born at the start of this century, during the coming decades that will serve as the

signposts of their lives—2030, 2050, 2070, and beyond.

comments:

(1) when I first attempted to purchase this book, it was sold out everywhere. So you might wish to watch this interview with Chris Hedges and Alfred McCoy.

(2) BUY THIS BOOK. Why? It corrects much of misinformation taught during my primary and secondary school history classes. For example: I was taught that European

Christians expanded throughout the new worlds which benefited poor uneducated indigenous peoples. But the truth is this: members of the Iberian World Order had received a

papal bill from the Vatican which granter explorers permission to take all non-Christians into perpetual slavery. {{{ I suspect that Jesus would not be amused }}}

Mission Economy (2021) Mariana Mazzucato

subtitled: A Moonshot Guide to Changing Capitalism

Capitalism is in crisis. The rich have gotten richer—the 1 percent, those with more than $1 million, own 44 percent of the world's wealth—while climate change is transforming—and in some cases wiping out—life on the planet. We are plagued by crises threatening our lives, and this situation is unsustainable. But how do we fix these problems decades in the making? Mission Economy looks at the grand challenges facing us in a radically new way. Global warming, pollution, dementia, obesity, gun violence, mobility—these environmental, health, and social dilemmas are huge, complex, and have no simple solutions. Mariana Mazzucato argues we need to think bigger and mobilize our resources in a way that is as bold as inspirational as the moon landing -- this time to the most ‘wicked’ social problems of our time. We can only begin to find answers if we fundamentally restructure capitalism to make it inclusive, sustainable, and driven by innovation that tackles concrete problems from the digital divide, to health pandemics, to our polluted cities. That means changing government tools and culture, creating new markers of corporate governance, and ensuring that corporations, society, and the government coalesce to share a common goal. We did it to go to the moon. We can do it again to fix our problems and improve the lives of every one of us. We simply can no longer afford not to.

Author, Mariana Mazzucato PhD writes:

- the Apollo Manned Space program (a public-private partnership proposed by President John F

Kennedy) did more to stimulate the American economy than all other activities, both public and private, including defense spending to fund foreign wars.

- from page 80: [because of government investment] computers went from "30 tons and 160 kilowatts in ENIAC" to "70 pounds and 70 watts in the AGC (Apollo Guidance Computer)"

- recall that it was NASA's manned space programs that created:

- the integrated circuit (chip) industry to build the Apollo Guidance Computer

(which was more mini than micro)

- the mini-computer industry (IBM and the seven dwarfs)

- the micro-computer industry which resulted in personal computers, tablets, and smart phones

- the software industry to supply the Apollo Guidance Computer with fault tolerant software

- all these were all instrumental in creating ARPANET which later became the internet.

- the integrated circuit (chip) industry to build the Apollo Guidance Computer

(which was more mini than micro)

- the South Korean government invested the tiny sum of 100 Million dollars into the Korean electronics industry with the intent of making Korea the leading manufacturer of digital displays like large screen televisions, computer monitors and cameras. That investment paid off in unexpected ways including the development of technology that created the smart phone business which they now own.

- five myths

- Myth 1: Businesses create value and take all the risks; governments only de-risk and facilitate

- Myth 2: The purpose of government is to fix market failures

- Myth 3: Government needs to run like a business

- Myth 4: Outsourcing saves money and lowers risk

- Myth 5: Government's pick winner

Pandemic 1918 (2018) Catharine Arnold

subtitled: Eyewitness Accounts from the Greatest Medical Holocaust in Modern History

- This book was a shocker for me because I thought I knew everything I needed to know about the great influenza pandemic of 1918 (and 1919) but I was wrong.

- The parallels between the influenza pandemic of 1918 and COVID-19 are stocking in that humanity has not learned a damned thing since then

- A Few Excerpts:

- since people had previously experienced influenza in 1916 and 1917, many shrugged then ignored warnings about this new flu which included a killer component: most patients literally drowned of pneumonia which set in during recovery (some people survived with ventilators)

- many people also ignored warnings that a second wave might be worse (in fact, the world-wide total number of influenza deaths between 1918 and 1919 approach 100 million which is ~ 5% of all humanity)

- most people, except those in the Red Cross, did not think to control infection transmissibility with masks. But people who wore masks fared much better and the photos of mask-wearing police officers directing traffic should be a warning to us all

- American organizations were formed to sue the federal government as well as the state of California for violating citizen's constitutional rights. One slogan read "Give me liberty or give me death" (many adherents received both)

- Manchester politicians ignored advice to cancel public armistice celebrations. After the party, a second wave took off resulting in many infections and 300 deaths.

- links:

Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid (1980) Douglas R Hofstadter

a great summer read while contemplating life and COVID-19I pulled this down from my bookshelf (on the recommendation of a friend) and cannot believe I am experiencing the same joy today that I first experienced 40 years ago (some books are timeless)

Permanent Record (2019) Edward Snowden

highly recommended for all citizensWhatever you previously thought about Edward Snowden will be changed for the better after you read this book. (full disclosure, I had no intention of reading this book until I watched the Oliver Stone movie titled "Snowden" in 2020)

Why Trust Science? (2019) by Naomi Oreskes

Why the social character of scientific knowledge is the reason why we can trust it

Do doctors really know what they are talking about when they tell us vaccines are safe? Should we take climate experts at their word when they warn us about the perils of global warming? Why should we trust science when our own politicians don't? In this landmark book, Naomi Oreskes offers a bold and compelling defense of science, revealing why the social character of scientific knowledge is its greatest strength "and the greatest reason we can trust it. Tracing the history and philosophy of science from the late nineteenth century to today, Oreskes explains that, contrary to popular belief, there is no single scientific method. Rather, the trustworthiness of scientific claims derives from the social process by which they are rigorously vetted. This process is not perfect -nothing ever is when humans are involved - but she draws vital lessons from cases where scientists got it wrong. Oreskes shows how consensus is a crucial indicator of when a scientific matter has been settled, and when the knowledge produced is likely to be trustworthy. Based on the Tanner Lectures on Human Values at Princeton University, this timely and provocative book features critical responses by climate experts Ottmar Edenhofer and Martin Kowarsch, political scientist Jon Krosnick, philosopher of science Marc Lange, and science historian Susan Lindee, as well as a foreword by political theorist Stephen Macedo.

How to Change Your Mind (2018/2019) Michael Pollan

Midway through the twentieth century, two unusual new molecules, organic compounds with a striking family resemblance, exploded upon the West. In time, they would change the course of social, political, and cultural history, as well as the personal histories of the millions of people who would eventually introduce them to their brains. As it happened, the arrival of these disruptive chemistries coincided with another world historical explosion—that of the atomic bomb. There were people who compared the two events and made much of the cosmic synchronicity. Extraordinary new energies had been loosed upon the world; things would never be quite the same. The first of these molecules was an accidental invention of science. Lysergic acid diethylamide, commonly known as LSD, was first synthesized by Albert Hofmann in 1938, shortly before physicists split an atom of uranium for the first time. Hofmann, who worked for the Swiss pharmaceutical firm Sandoz, had been looking for a drug to stimulate circulation, not a psychoactive compound. It wasn’t until five years later when he accidentally ingested a minuscule quantity of the new chemical that he realized he had created something powerful, at once terrifying and wondrous. The second molecule had been around for thousands of years, though no one in the developed world was aware of it. Produced not by a chemist but by an inconspicuous little brown mushroom, this molecule, which would come to be known as psilocybin, had been used by the indigenous peoples of Mexico and Central America for hundreds of years as a sacrament. Called teonanácatl by the Aztecs, or “flesh of the gods,” the mushroom was brutally suppressed by the Roman Catholic Church after the Spanish conquest and driven un- derground. In 1955, twelve years after Albert Hofmann’s discovery of LSD, a Manhattan banker and amateur mycologist named R. Gordon Wasson sampled the magic mushroom in the town of Huautla de Jiménez in the southern Mexican state of Oaxaca. Two years later, he published a fifteen-page account of the “mushrooms that cause strange visions” in Life magazine, marking the moment when news of a new form of consciousness first reached the general public. (In 1957, knowledge of LSD was mostly confined to the community of researchers and mental health professionals.) People would not realize the magnitude of what had happened for several more years, but history in the West had shifted.interviews with the author:

1) https://www.sciencefriday.com/articles/michael-pollan-on-the-psychedelic-renaissance/

2) https://www.npr.org/2019/05/24/726085011/reluctant-psychonaut-michael-pollan-embraces-new-science-of-psychedelics

America: The Farwell Tour (2018) Chris Hedges

If you are worried about the rise of populism in western politics, or are worried about the next economic crash then I suggest you read the book: America: The Farewell Tour (2018) Chris Hedges. If you do not have the inclination to read another book at this time, then watch one of these video interviews with the author.- https://tvo.org/video/programs/the-agenda-with-steve-paikin/the-collapse-of-the-american-empire

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=csI8JLJ15Ak The Collapse of the American Empire :: (CIGA) Centre for International Governance Innovation

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T_l4ucOeIkY ON CONTACT: America: The Farewell Tour

The Square and the Tower (2018) Niall Ferguson

subtitled: Networks and Power, From the Freemasons to Facebook

This is a book about human

networking. People who work in a large corporation (the tower) then later meet in a bar (the square) after working hours is one common example. Other examples

include: religious groups, guilds, trade unions, fraternities, and masonic lodges to only name a short list of many. So I suppose "the square" might also refer to the

draftsman's "set square" seen just under the compass and eye in the masonic lodge symbol pictured to the right.

This is a book about human

networking. People who work in a large corporation (the tower) then later meet in a bar (the square) after working hours is one common example. Other examples

include: religious groups, guilds, trade unions, fraternities, and masonic lodges to only name a short list of many. So I suppose "the square" might also refer to the

draftsman's "set square" seen just under the compass and eye in the masonic lodge symbol pictured to the right.

The author correctly mentions that the world is transitioning from vertical hierarchies (think China and Russia or the Papacy) to horizontal networks (think many of the Western democracies or Protestantism). Perhaps this is the biggest problem with Americans thinking that Russia interfered with the American presidential election of 2016: most Americans are not aware of the shift from vertical to horizontal. Putin is probably unaware of this as well.

Political Extremism in America: Don’t blame Russia, blame Facebook and Twitter

Video-1: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tv9JpGc1dgY (length: 3:42)

The Agenda with Steve Paikin

Video-2:

https://tvo.org/video/programs/the-agenda-with-steve-paikin/the-age-of-networks (length 29:51)

Quote (p96): The charter for The Royal Society [of London for Improving Natural Knowledge] was explicit in granting to its president, council and fellows (members), and their successors, the freedom 'to enjoy mutual intelligence and knowledge with all and all manner of strangers and foreigners, whether private or collegiate, corporate or politic, without any molestation, interruption, or disturbance whatsoever'. By contrast, the Académie des sciences in Paris was originally the private property of the crown. When it met for the first time on 22 December 1666, it was in the King's library and had an official policy of secrecy.

Comment: This is the first book I've read that has a non-conspiratorial description of the Illuminati (a group of Bavarian academics trying to promote the enlightenment between 1775 and 1785; yep only around for 10-years). Chapter-1 is titled "The Mystery of the Illuminati" while chapter-10 is titled "The Illuminati Illuminated". Ferguson explains that we would not know the name Illuminati if it were not for the Freemasons.

Benjamin Franklin: An American Life (2003) Walter Isaacson

highly recommended (also provides a unique view of life in prerevolutionary America)In this authoritative and engrossing full-scale biography, Walter Isaacson, bestselling author of Einstein and Steve Jobs, shows how the most fascinating of America's founders helped define our national character. Benjamin Franklin is the founding father who winks at us, the one who seems made of flesh rather than marble. In a sweeping narrative that follows Franklin’s life from Boston to Philadelphia to London and Paris and back, Walter Isaacson chronicles the adventures of the runaway apprentice who became, over the course of his eighty-four-year life, America’s best writer, inventor, media baron, scientist, diplomat, and business strategist, as well as one of its most practical and ingenious political leaders. He explores the wit behind Poor Richard’s Almanac and the wisdom behind the Declaration of Independence, the new nation’s alliance with France, the treaty that ended the Revolution, and the compromises that created a near-perfect Constitution. In this colorful and intimate narrative, Isaacson provides the full sweep of Franklin’s amazing life, showing how he helped to forge the American national identity and why he has a particular resonance in the twenty-first century.

Leonardo da Vinci (2017) Walter Isaacson

highly recommended (also provides a unique view of life in Renaissance Italy)Based on thousands of pages from Leonardo’s astonishing notebooks and new discoveries about his life and work, Walter Isaacson weaves a narrative that connects his art to his science. He shows how Leonardo’s genius was based on skills we can improve in ourselves, such as passionate curiosity, careful observation, and an imagination so playful that it flirted with fantasy.

A Mind at Play (2017) Jimmy Soni + Rob Goodman

subtitled: How Claude Shannon Invented the Information Age

VERY highly recommended (a must-have for "computer people")

In this elegantly written, exhaustively researched biography, Jimmy Soni and Rob Goodman reveal Claude Shannon’s full story for the first time. It’s the story of a small-town Michigan boy whose career stretched from the era of room-sized computers powered by gears and string to the age of Apple. It’s the story of the origins of our digital world in the tunnels of MIT and the “idea factory” of Bell Labs, in the “scientists’ war” with Nazi Germany, and in the work of Shannon’s collaborators and rivals, thinkers like Alan Turing, John von Neumann, Vannevar Bush, and Norbert Wiener.

Age of Discovery (2016) Ian Goldin + Chris Kutarna

subtitled: Navigating the Risks and Rewards of Our New Renaissance

To make sense of present shocks, we need to step back and recognize: we’ve been here before. The first Renaissance, the time of Columbus, Copernicus, Gutenberg and others, likewise redrew all maps of the world, democratized communication and sparked a flourishing of creative achievement. But their world also grappled with the same dark side of rapid change: social division, political extremism, insecurity, pandemics and other unintended consequences of discovery. Now is the second Renaissance. We can still flourish―if we learn from the first.

The Undoing Project (2016) Michael Lewis

Forty years ago, Israeli psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky wrote a series of breathtakingly original studies undoing our assumptions about the decision-making process. Their papers showed the ways in which the human mind erred, systematically, when forced to make judgments in uncertain situations. Their work created the field of behavioral economics, revolutionized Big Data studies, advanced evidence-based medicine, led to a new approach to government regulation, and made much of Michael Lewis's own work possible. Kahneman and Tversky are more responsible than anybody for the powerful trend to mistrust human intuition and defer to algorithms.

Science Under Siege (2015) CBC Radio

highly recommended for all citizensNot a book; This is a series of CBC radio programs aired first June-2015 on "Ideas" with Paul Kennedy

Are we living through an Anti-Scientific Revolution? Scientists around the world are increasingly restricted in what they can research, publish and say -- constrained by belief and ideology from all sides. Historically, science has always had a thorny relationship with institutions of power. But what happens to societies which turn their backs on curiosity-driven research? And how can science lift the siege? CBC Radio producer Mary Lynk looks for some answers in this three-part series.

- Science Under Siege, Part 1 :: Dangers of Ignorance - airs Wednesday, June 3, 2015

- http://www.cbc.ca/radio/ideas/science-under-siege-part-1-1.3091552

- Explores the historical tension between science and political power and the sometimes fraught relationship between the two over the centuries. But what happens when science gets sidelined? What happens to societies which turn their backs on curiosity-driven research?

- Science Under Siege, Part 2 :: The Great Divide - airs Thursday, June 4, 2015

- http://www.cbc.ca/radio/ideas/science-under-siege-part-2-1.3098865

- Explores the state of science in the modern world, and the expanding -- and dangerous -- gulf between scientists and the rest of society. Many policy makers, politicians and members of the public are giving belief and ideology the same standing as scientific evidence. Are we now seeing an Anti-Scientific revolution? A look at how evidence-based decision making has been sidelined.

- Science Under Siege, Part 3 :: Part 3: Fighting Back - airs Friday, June 5, 2015

- http://www.cbc.ca/radio/ideas/science-under-siege-part-3-1.3101953

- Focuses on the culture war being waged on science, and possible solutions for reintegrating science and society. The attack on science is coming from all sides, both the left and right of the political spectrum. How can the principle of direct observation of the world, free of any influence from corporate or any other influence, reassert itself? The final episode of this series looks at how science can withstand the attack against it and overcome ideology and belief.

- Podcasts: http://www.cbc.ca/radio/podcasts/documentaries/the-best-of-ideas/

Comment: in part one I learned that the reason why Europe leaped ahead of China four hundred years ago was primarily due to the work of Francis Bacon who convinced the English government to:

- allow scientists to publish freely without requiring the preapproval of a government censor (as was the case in places like Italy and China)

- actively promote scientific research by funding education, universities, and scientific organizations like The Royal Society which was formed in 1660 under a royal charter by King Charles II

Capital in the Twenty-First Century (2014) Thomas Piketty

At the very minimum, the Introduction to this book should be required reading for every citizen in the western world. The remainder of the book extends the work of Adam Smith (the first economist) and John Maynard Keynes (the first macro economist).

Links:

-

www.amazon.com/Capital-Twenty-First-Century-Thomas-Piketty/dp/067443000X/

- click on the book icon: LOOK INSIDE

- Read the Introduction

- http://piketty.pse.ens.fr/en/capital21c2 - Supporting material for the book

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7TLtXfZth5w - Capital in the Twenty-First Century

Excerpts from Section 3, Chapter 7 "Inequality and Concentration: Preliminary Bearings"

- Since there are no formal definitions of "upper class", "middle class", "lower class", many economists just divide the population into thirds

- Piketty uses "top 10%", "middle 40%", and "bottom 50%" so he can better compare European and American societies over the past 200+ years.

- According to Piketty, extreme inequality almost always contributes to, or triggers, conflict (the French Revolution is one example)

- http://piketty.pse.ens.fr/files/capital21c/en/pdf/T7.1.pdf Inequality of

labor income across time and space which I have excerpted here so I can insert highlights

Class Name Category

By SizeInequality of Capital Labor Income Scandinavia

1970-1980Europe

2010USA

2010USA

2030

(?)Upper Class top 10% 20% 25% 35% 45% Middle Class middle 40% 45% 45% 40% 35% Lower Class bottom 50% 35% 30% 25% 20% Gini coefficient 0.19 0.26 0.36 0.46 - Comments:

- Apparently the USA already has the highest level of inequality of the western world but is projected to get much worse

- Comparing the USA (2010) to Scandinavia (1970s-1980s), the societies appear inverted

- http://piketty.pse.ens.fr/files/capital21c/en/pdf/T7.3.pdf Inequality of total income across time and space

- http://piketty.pse.ens.fr/files/capital21c/en/pdf/T7.2.pdf Inequality of

capital ownership across time and space

which I have excerpted here so I can insert highlightsClass Name Category

By SizeInequality of Capital Ownership Scandinavia

1970-1980Europe

2010USA

2010Europe

1910Upper Class top 10% 50% 60% 70% 90% Middle Class middle 40% 40% 35% 25% 5% Lower Class bottom 50% 10% 5% 5% 5% Gini coefficient 0.58 0.67 0.73 0.85 - Comments:

- the middle class (40% by size) owned 40% in egalitarian Scandinavia

- upper class (10% by size) owns 50% (flipped?)

- lower class (50% by size) owns 10% (flipped?)

- notice how the lower class never seems to drop lower than 5%

- notice how the middle class also hit a 5% wall in 1910 Europe (could the 5% mark represent a boundary for extreme capitalism?)

- the middle class (40% by size) owned 40% in egalitarian Scandinavia

Comments and General Observations

- Piketty provides good reasons why progressive income taxes and progressive estate taxes were introduced to deal with inequities

with triggered the French Revolution

- comment: in theory, everyone resents the government that appears to swoop in for their cut after the death of a parent. But the best way to think about this is to remember the members of the first estate (church) and the second estate (nobility) were sitting on a lot of wealth while paying no taxes at all. So to be far, everyone should feel it a civic duty to pay income and estate taxes. It's patriotic.

- If you share the view of many that the economy is a complicated machine and capital is the lubricant then you are forced to this logical conclusion: concentrating too much capital in the hands of too few will cause the machine to seize. In essence, lack of lubricant slowed economic recovery after the crash-of-1929; The ramp up of: progressive income taxes, estate taxes, and preparation for world-war-2 put more lubricant back into the American machine

- Example triggering events (from me):

- Britain's military expenditures throughout the world in the middle 1700s caused financial problems at home which the British parliament attempted to shift to their colonies. The Tea Act was one example and this was one of the triggers of the American Revolution. (no taxation without representation)

- France's expenditures (including financial and military support of the American Revolution) caused extreme inequality in France (population of 30 million) which triggered the French Revolution

- The Russian Empire's expenditures (including financial and military contributions to World War One) caused extreme inequality which triggered the final Russian Revolution in 2017

- Assigning sole blame for World War One to Germany (even though it was triggered by the assassination of Austrian Arch Duke Ferdinand in Sarajevo -AND- was complicated by the actions of many countries miscommunicating) brought huge reparation payments. This triggered extreme poverty in Germany which lead to the rise of Hitler and the madness which followed.

- Food for thought

- France's support of the American Revolution was approved by the Emperor with the support of the nobility (who were both of the second estate) who paid no taxes. It was citizens (the third estate) who paid taxes that felt the brunt of the poor decisions made by upper-class twits.

- Russia's support of World War One (defending the Kingdom of Serbia which was attacked by Austria-Hungary in retaliation for the assassination of Franz Ferdinand) was fully approved by an enthusiastic Tsar Nicholas II who grossly mismanaged the war effort. Once again, it was the citizenry who shouldered the burden.

- Most people seem to have missed the point that the American Tea Party movement started in 2008 when many citizens were seeing government bailouts of Wall Street but no similar bailouts of Main Street. The parallels between pre-revolutionary France and modern day America are strikingly similar with very rich Americans taking on the role of the French Nobility (they want a say but they do not want to pay). To make matters worse, modern American society is fully armed; many with military-style assault weapons. Unless something is done to stop inequality, I fear there is trouble on the horizon.

- Apparently the largest amounts of pay-inequity are coming from English-speaking countries (United States, Britain, Canada, Australia) where super-managers have their

invisible hand legally in the till. Many people in the west concoct various justification stories, and here are a few:

- corporate success is due to technology-related increases in productivity (which ignores the fact that the same technology is available to non-English speaking countries).

- larger compensation packages are required so we can hire the best talent (which ignores the demand-supply curve taught in Economics-101; if the supply of CEOs is large then this oversupplu should result in lower pay, not higher)

- We have all heard another justification which is "pay for performance" but we all know that all lot of what happens may be due to luck.

- In 1776, moral philosopher Adam Smith published his theories of capitalism in The Wealth of Nations to assist with social/societal problems appearing at the beginning of the Industrial Revolution. Over my short 60 years on planet Earth, I have heard numerous western capitalists quote selected one-liners from Wealth of Nations while failing to mention other issues in that book (like productivity, division of labor, accumulation of inherited wealth, etc.) and this has resulted in a form of extreme capitalism I am certain Adam Smith never imagined. Furthermore, most people today would agree that Industrial Revolution has been largely replaced by the Information Age which means humanity now requires a kinder gentler form of capitalism than what we have seen so far. I am certain there are many capitalists who disagree but but let me point out that Smith never imagined globalization. If he were publishing his magnum opus today it would have been titled Wealth of Humanity. Perhaps Piketty's book will eventually be seen as a follow-on to Wealth of Nations

The Entrepreneurial State: (2013) Mariana Mazzucato

subtitled: Debunking Public vs. Private Sector Myths

Okay so on of the biggest myths popularized in the past 30-years that government gets in the way of business. This book is proof that this myth is false. In reality, governments do the lion's share of all the research while assuming all the risk. It is only at this point when corporate entrepreneurs step in to take credit for all the innovation.

Publisher's Blurb: This new bestseller from leading economist Mariana Mazzucato – named by the ‘New Republic’ as one of the ‘most important innovation thinkers’ today – is stirring up much-needed debates worldwide about the role of the State in innovation. Debunking the myth of a laggard State at odds with a dynamic private sector, Mazzucato reveals in case study after case study that in fact the opposite situation is true, with the private sector only finding the courage to invest after the entrepreneurial State has made the high-risk investments. Case studies include examples of the State’s role in the ‘green revolution’, in biotech and pharmaceuticals, as well as several detailed examples from Silicon Valley. In an intensely researched chapter, she reveals that every technology that makes the iPhone so ‘smart’ was government funded: the Internet, GPS, its touch-screen display and the voice-activated Siri. Mazzucato also controversially argues that in the history of modern capitalism the State has not only fixed market failures, but has also shaped and created markets, paving the way for new technologies and sectors that the private sector only ventures into once the initial risk has been assumed. And yet by not admitting the State’s role we are socializing only the risks, while privatizing the rewards in fewer hands. This, she argues, hurts both future innovation and equity in modern-day capitalism. Named one of the ‘2013 Books of the Year’ by the ‘Financial Times’ and recommended by ‘Forbes’ in its 2013 ‘creative leaders’ list, this book is a must-read for those interested in a refreshing and long-awaited take on the public vs. private sector debate.

Some Example Successes: RADAR, SONAR, aerospace, space flight, microelectronics, internet, IT-revolution, GPS, biotech, nanotech, clean-tech. Today, ARPAe (ARPA energy) is responsible for the lion's share of new energy research.

The Republican Brain (2012) Chris Mooney

subtitled: The Science of Why They Deny Science and Reality

Bestselling author Chris Mooney uses cutting-edge research to explain the psychology behind why today’s Republicans ("conservatives" for those people outside of the USA)

reject reality—it's just part of who they are.

From climate change to evolution, the rejection of mainstream science among Republicans is growing, as is the denial of expert consensus on the economy, American history, foreign policy and much more. Why won't Republicans (conservatives) accept things that most experts agree on? Why are they constantly fighting against the facts?

Science writer Chris Mooney explores brain scans, polls, and psychology experiments to explain why conservatives today believe more wrong things; appear more likely than Democrats ("liberals" for those people outside of the USA) to oppose new ideas and less likely to change their beliefs in the face of new facts; and sometimes respond to compelling evidence by doubling down on their current beliefs.

-

Goes beyond the standard claims about ignorance or corporate malfeasance to discover the real, scientific reasons why Republicans reject the widely accepted findings of mainstream science, economics, and history—as well as many undeniable policy facts (e.g., there were no “death panels” in the health care bill).

-

Explains that the political parties reflect personality traits and psychological needs—with Republicans more wedded to certainty, Democrats to novelty—and this is the root of our divide over reality.

-

Written by the author of The Republican War on Science, which was the first and still the most influential book to look at conservative rejection of scientific evidence. But the rejection of science is just the beginning…

Certain to spark discussion and debate, The Republican Brain also promises to add to the lengthy list of persuasive scientific findings that Republicans reject and deny.

Comments:

- This book has nothing to do with intelligence or so-called "theories involving hard-wiring of the brain" (because the human brain is hardwired to be

soft-wired). For those who think in terms of "nature vs. nurture" it might be wise to think in terms of "nature and nurture". Why?

- nurture plays a roll since we initially learn from those around us, and these people tend to be parents. On the flip side, early ideas might be unlearned by expanding beyond our local groups as usually happens when shipped off to college

- nature plays by changing the size and shape of various brain regions (like the amygdala which is the seat of emotions vs. the anterior cingulate which orchestrates reasoning)

- Do not read this book if you think you can change the other side. Like the Amish, they have all your facts but have come to different conclusions. If change comes it will be their personal decision.

- Do read this book if you are curious as to why conservatives think-what-they-think, say-what-they-say, and believe-what-they-believe

- The author gives evidence to support the assertion that, on average, your liberalism dial increases as you become more educated. On the flip side, your conservative dial increases as you become more wealthy. I'm not sure which takes precedent when you are both educated and wealthy.

- The author gives evidence to support the assertion that, on average, conservatives tend to see issues as black-or-white while liberals tend to see issues as shades-of-gray. He also quotes conservative publishers who support this claim. I wonder if a liberal US president would have authorized attacking Iraq in 2003 on the flimsy evidence surrounding WMDs (Weapon's of Mass Destruction) which turned out to be nonexistent.

- Conservatives play politics as a team sport (maybe twice as much as liberals). If a conservative team member says something stupid, conservatives tend to collectively circle the wagons rather than publically criticizing. Meanwhile if a liberal says something stupid then this error will be criticized by both sides (much to the delight of conservatives)

- My Observations: almost everyone alive today has some difficulty understanding arguments used by the Roman

Catholic Church (between 1610 and 1633) against Galileo who dared publish a book claiming "the Earth was not the center of the universe".

- First off, it is plain to all that Galileo was the role of "liberal" in this debate while the Church was playing the role of "conservative".

If we were only talking about religion, then Jesus played the liberal role (change) while the Sanhedrin played conservative (status quo). - Secondly, the arguments used by the church only make sense if they were using "their own facts". Which set of facts "were more correct" could have been solved by simply staying up late a few evenings to view (through a telescope) four moons orbiting Jupiter. But there are no records indicating representatives of the Church ever did this. So in the final analysis this affair was managed as if hosted by lawyers rather than scientists.

- Likewise, today we see arguments where each side presents "their own facts" from "their own experts" on issues like "vaccines" and "climate change" which could be resolved by doing further observational tests (reading peer reviewed publications from qualified experts who employed the scientific method first published by Francis Bacon then popularized by Isaac Newton). Not doing this places us firmly in the same lawyer-vs-scientist conflict as happened ~ 400 years ago.

- Many political people today see the modern world in a binary split between left/liberal and right/conservative which appears to ignore the fact that perhaps 60% of society is located squarely in the center

- In my community it appears that liberals seem happier than conservatives. In fact, there isn't a day that goes by when I don't hear a conservative complain about something then go on to claim that life would be better if only {whatever} changed.

- First off, it is plain to all that Galileo was the role of "liberal" in this debate while the Church was playing the role of "conservative".

Tear Down This Myth (2010) Will Bunch

subtitled: The Right-Wing Distortion of the Reagan Legacy

So the other day I was exercising at the gym while a poorly educated (you could tell by the grammar) right-wing nut-bar next to me preached a pro-conservative sermon about

Saint Ronald Reagan, savior of the free world. I am apolitical so did not offer any counterpoints; but it would have been pointless anyway because you can never argue with

"true believers" (especially those who only see politics as a team sport but are unable to articulate the differences between "progressive conservatives" like Churchill and

"big business conservatives" like Thatcher and Reagan). While "this preacher" droned on I kept thinking: isn't this the same guy who "fired the air traffic controllers

which signaled everyone else that it was okay to attack unions and the middle class", "who's free-trade policies resulted in the creation of a new American phrase: the rust

belt", "diverted money from Iran to the contras in Nicaragua then lied about it", "allowed the just-broken

up Bell System to begin shifting back in the direction of a monopoly", "instituted Reaganomics (also called the trickle-down economics)", "who's policies ended up creating

the Savings and Loan crisis", "created the Strategic

Defense Initiative also known as Star Wars (I still remember Caspar Weinberger looking on in stunned silence during the announcement)", "added 2 trillion to the

nation's debt"?

Later that evening I was Goggling some stuff about Reagan when I stumbled on this book: Tear Down This Myth: The Right-Wing Distortion of the Reagan Legacy which is obviously titled after Reagan's famous speech where he said "Mister Gorbachev. Tear down this wall". So I bought the book (even though I am apolitical) which turned out to be a very good read as well as a refresher about American and world history between 1981 and 1988. But even if you don't buy this book, take some time to read the reviews here: https://www.amazon.com/Tear-Down-This-Myth-Right-Wing/dp/1416597638/

Idea Man: A Memoir by the Cofounder of Microsoft (2011) Paul Allen

- I didn't know that minicomputers were the key to Microsoft's 8-bit BASIC. Apparently all target micro platforms were simulated on minis. Gates and Allen started doing this at Harvard when they wrote Altair 8800 BASIC on a DEC PDP-10 running TOPS-10. They continued this in Albuquerque by leasing PDP-10 time from local schools. When they moved to Washington they decided to buy a brand new DECSYSTEM-20

- I didn't know that Microsoft wrote TRS-80 BASIC (for the Radio Shack "a.k.a. Trash 80"); Commodore BASIC for the Commodore PET; and AppleSoft BASIC for the Apple2 (a.k.a. Apple II plus )

- I skipped over the few chapters related to "owning sports teams" because I don't care about that stuff

Steve Jobs (2011) Walter Isaacson

Shocking revelations:

- giving a speech to university students telling them the secret to success is "loss of virginity" and "consuming LSD" (wtf?)

- constantly crying through-out his whole life. (was this due to LSD or unhappiness related to a vegan diet?)

- studied Zen Buddhism and meditated throughout his life but appeared to be the most materialistic person in North America (and a first-class prick)

- appeared to hate the social imperatives of the French (re: Danielle Mitterrand's questions during her tour of the Macintosh factory) and yet thought of himself as an artist and considered living in Paris.

- accused others, including Microsoft, of stealing Apple's ideas then released adverts with quotes like "good artists copy, but great artists steal"

- add to this the fact that the whole mouse-based graphical interface was stolen from Xerox

- telling people "their software was crap" when he himself did not know how to write a computer program

- closing the Macintosh architecture just after IBM opened the PC architecture (IBM was attempting to emulate the openness of the Apple 2)

then having the gall to release an advert suggesting IBM was like "big brother" in George Orwell's book 1984 while Apple was in the role of the athletic woman smashing the screen.

- Sticking with 1984 as a metaphor:

- it was Jobs who projected the cult of personality

- it was Jobs who was the purveyor of newspeak and doublethink (see IBM comment above)

- it was Jobs who engaged in propaganda and historical revisionism

- if Big Brother actually existed, he would have been envious of Jobs' Reality Distortion Field

- I am convinced dropping LSD would produce many more societal dropouts than corporate success stories. Do not follow his example

- Throughout the book, I thought "either Jobs was constantly on LSD, or was bipolar, or schizophrenic, or all three". But the remark about Narcissistic Personality Disorder on page 266 seemed to hit the mark.

- Why are people still referring to this guy as a genius? True Apple talent could be found in people like Steve Wozniak, Bill Atkinson, and Andy Hertzfeld to only name three of many. Wozniak is fond of saying that he would be nowhere without Jobs but I think he is wrong. Wozniak would have eventually hooked up with someone less egocentric while more humane.

- Steve Jobs told everyone he was a Buddhist. I hope he believed in Karma and I hope he will be reborn as a software developer who will work for an immature boss who drops LSD and throws temper-tantrums

Thomas Paine's Rights of Man (2008) Christopher Hitchens

subtitled: Books That Changed the World

Thomas

Paine's critique of monarchy and introduction of the concept of human rights influenced both the French and the American revolutions, argues Vanity Fair contributor and

bestselling author Hitchens (God Is Not Great) in this incisive addition to the Books That Changed the World series. Paine's ideas even influenced later

independence movements among the Irish, Scots and Welsh. In this lucid assessment, Hitchens notes that in addition to Common Sense's influence on Jefferson and the

Declaration of Independence, Paine wrote in unadorned prose that ordinary people could understand. Hitchens reads Paine's rejection of the ministrations of clergy in his

dying moments as an instance of his unyielding commitment to the cause of rights and reason. But Hitchens also takes Paine to task for appealing to an idealized state of

nature, a rhetorical move that, Hitchens charges, posits either a mythical past or an unattainable future and, Hitchens avers, disordered the radical tradition thereafter.

Hitchens writes in characteristically energetic prose, and his aversion to religion is in evidence, too. Young Paine found his mother's Anglican orthodoxy noxious, Hitchens

notes: Freethinking has good reason to be grateful to Mrs Paine.

Thomas

Paine's critique of monarchy and introduction of the concept of human rights influenced both the French and the American revolutions, argues Vanity Fair contributor and

bestselling author Hitchens (God Is Not Great) in this incisive addition to the Books That Changed the World series. Paine's ideas even influenced later

independence movements among the Irish, Scots and Welsh. In this lucid assessment, Hitchens notes that in addition to Common Sense's influence on Jefferson and the

Declaration of Independence, Paine wrote in unadorned prose that ordinary people could understand. Hitchens reads Paine's rejection of the ministrations of clergy in his

dying moments as an instance of his unyielding commitment to the cause of rights and reason. But Hitchens also takes Paine to task for appealing to an idealized state of

nature, a rhetorical move that, Hitchens charges, posits either a mythical past or an unattainable future and, Hitchens avers, disordered the radical tradition thereafter.

Hitchens writes in characteristically energetic prose, and his aversion to religion is in evidence, too. Young Paine found his mother's Anglican orthodoxy noxious, Hitchens

notes: Freethinking has good reason to be grateful to Mrs Paine.

RELENTLESS: True Story of Ted Rogers (2008) Ted Rogers

- As president and CEO of Rogers Communications Inc., Ted Rogers is at the head of a communications and media company that operates Canada’s largest wireless carrier, its largest cable provider, 53 radio stations, 70 consumer and trade magazines, the OMNI and CityTV networks, and other properties as diverse as The Shopping Channel and the Toronto Blue Jays. Outspoken, sometimes controversial and always forward-thinking, Rogers is a legendary innovator whose brand stands among the top in Canadian business. Now, for the first time, Ted Rogers tells the story of how he built Rogers Communications into one of the largest companies in Canadian history—and in only one generation. The tragic, premature death of his father, radio pioneer Ted Rogers Sr., left his family with little except the burning desire to reclaim what they had lost. From an early age, Ted was fascinated with radio and television; he once strung wires out of his dorm room to a roof-top antenna to bring in U.S. programming to Toronto before the city had any stations. As a law student, he invested everything he had in an FM station, buying CHFI when only five percent of the market actually owned an FM radio. Success with CHFI led to the creation of Agincourt TV station CFTO. Rogers is characteristically frank about his successes and his failures. Over the years, he has faced challenges to his domain, sometimes risking so much that it nearly cost him everything. Each time, however, he has returned stronger than ever. Written in a highly accessible style, A Practical Dreamer will appeal as much to Main Street as to Bay Street. Filled with backroom deals, on-air battles and the often outrageous exploits of this communications visionary, A Practical Dreamer will ring true as the most fascinating business memoir of the year.

- CFRB = Canada's First Rogers Batteryless

- CFTR = Canada's First Ted Rogers

- Ted Rogers Senior was the inventor of the A. C. Vacuum Tube (a.k.a. Alternating Current Valve).

http://www.ieee.ca/diglib/library/electricity/pdf/P_one_2.pdf

Note: this following information was not described in this book:- Prior to the development of the A. C. Vacuum Tube, radio transmitters and receivers were powered with three battery strings. The "A" string was used to power the

filament (a.k.a. cathode), the "B" string was used to power the anode, the "C" string was used to bias control grid. When your table-top radio was dead, you had to

take it to the local radio shop for repair (or call the local neighborhood geek)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battery_(vacuum_tube) - Before Rogers' invention a naked filament acted as the cathode. Rogers modified the cathode by replacing the filament with a metal emitter which is only heated by the filament. Since the filament is electrically isolated from the emitter, it can now be powered by A. C. rather than D. C.

- Prior to the development of the A. C. Vacuum Tube, radio transmitters and receivers were powered with three battery strings. The "A" string was used to power the

filament (a.k.a. cathode), the "B" string was used to power the anode, the "C" string was used to bias control grid. When your table-top radio was dead, you had to

take it to the local radio shop for repair (or call the local neighborhood geek)

Edward Samuel Rogers and the Revolution of Communications (2000) by Ian A. Anthony

- A book about Edward (Ted) Rogers Sr. and his contributions to radio communications including the A. C. Vacuum Tube and Toronto radio station CFRB (Canada's First Rogers Batteryless)

Valley Boy (2007) Tom Perkins

- This guy is somewhat of a cool character with an EE-CS from MIT and an MBA from Harvard.

- He made his first million by setting up a company named University Laboratories Inc. to manufacture and sell research lasers. His next big success was to transform Hewlett-Packard's computer division into a world wide megalith. After that he was involved in the creation of Tandem Computers. As a venture capitalist, he was behind Compaq, Genentech, SUN Microsystems, and Google.

iWoz (2006) Steve Wozniak and Gina Smith

- Steve Wozniak designed the Apple-1 and Apple-2 single handedly with no help from anyone else

- Steve Jobs is an enabler:

- He enabled Apple to startup as a company

- He convinced Wozniak to quit HP and work fulltime at Apple

- He convinced Wozniak to use Alan Shugart's new 5.25 inch (13.3 cm) floppy disk drive in Wozniak's Apple DOS system

- How could a cool technology engineering company have morphed into a technology marketing company?

- When I read how the Apple-3 and Macintosh employees basically dumped upon the Apple-2 employees (who were carrying everyone else), I was reminded of one of the chapters of "Inside Stupidity" where many companies produce products to compete with themselves. It's almost like the egos of the "incoming suits" in are trying to trump the efforts of the "outgoing bluegenes" and all other issues are secondary.

The European Dream (2005) Jeremy Rifkin

subtitled: How Europe's Vision of the Future Is Quietly Eclipsing the American Dream

The American Dream is in decline. Americans are increasingly overworked, underpaid, and squeezed for time. But there is an alternative: the European Dream

- a more leisurely, healthy, prosperous, and sustainable way of life. Europe's lifestyle is not only desirable, argues Jeremy Rifkin, but may be crucial to sustaining

prosperity in the new era. With the dawn of the European Union, Europe has become an economic superpower in its own right-its GDP now surpasses that of the United States.

Europe has achieved newfound dominance not by single-mindedly driving up stock prices, expanding working hours, and pressing every household into a double- wage-earner

conundrum. Instead, the New Europe relies on market networks that place cooperation above competition; promotes a new sense of citizenship that extols the well-being of the

whole person and the community rather than the dominant individual; and recognizes the necessity of deep play and leisure to create a better, more productive, and healthier

workforce. From the medieval era to modernity, Rifkin delves deeply into the history of Europe, and eventually America, to show how the continent has succeeded in slowly

and steadily developing a more adaptive, sensible way of working and living. In The European Dream, Rifkin posits a dawning truth that only the most jingoistic can ignore:

Europe's flexible, communitarian model of society, business, and citizenship is better suited to the challenges of the twenty-first century. Indeed, the European Dream may

come to define the new century as the American Dream defined the century now past.

quote: "Europeans should congratulate themselves for producing the most humane approach to capitalism ever attempted"

For a fair economic comparison of the USA to Europe the author asserts that you must create a table comparing "American States" to European "Countries" (think

"United States of Europe") ordered by economic output, then compare the entries line-by-line. Here is a partial list taken from data found on pages

65-66. Notice how Europe wins every time? Why do Americans continue to believe they are number one in everything?

| European Country |

GDP (US Billion) |

GDP (US Billion) |

American State |

|---|---|---|---|

| Germany | $1,866 | $1,344 | California |

| United Kingdom | $1,400 | $799 | New York |

| France | $1,300 | $742 | Texas |

| Italy | $1,000 | $472 | Florida |

| Spain | $560 | $467 | Illinois |

| Netherlands | larger | smaller | New Jersey |

| Sweden | larger | smaller | Washington |

| Belgium | larger | smaller | Indiana |

| Austria | larger | smaller | Minnesota |

| Poland | larger | smaller | Colorado |

| Denmark | larger | smaller | Connecticut |

| Finland | larger | smaller | Oregon |

| Greece | larger | smaller | South Carolina |

- all numbers are in US dollars (2003-2004)

- only five rows of numbers were provided in the book but the reader is directed to external reference 3-19 titled: "A Comparison of the Top 25 United States GSPs with the Top 25 European Union GDPs" published by U.S. Department of Commerce: Bureau of Economic Analysis - November 15 2002 - www.bea.gov (Caveat: GSP is not a typo; it means Gross State Product which is now classified as a Gross Regional Domestic Product)

- Click here for recent numbers:

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Comparison_between_U.S._states_and_countries_by_GDP_(nominal) (why was this deleted in 2019?)

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_U.S._states_and_territories_by_GDP

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lists_of_sovereign_states_and_dependent_territories#Gross_domestic_product

- Click here for a 2023 report titled: "The European Union’s remarkable growth performance relative to the United States"

- The American press is fond of calling Greece's economy as "a basket case". If this assessment is true then what should we say about US states, like South Carolina, or any others that didn't make this list?

- in 2016 the UK public voted (in a non-binding referendum) to leave the EU in a move called BREXIT

(British politicians later voted to make it binding)

- LEAVE took the majority in England and Wales.

- REMAIN took the majority in Scotland, Northern Ireland and Gibraltar.

- It appears that these differences will (eventually) shatter the United Kingdom into their respective countries thus signalling another end-of-empire

- the decision to leave was been attributed to right-wing populism (caused by a combination of "job losses due to automation" as well as "migrant immigration triggered by the military actions of Britain, France, and the USA which collectively brought down the governments of Iraq and Libya")

- so now we have a chance to perform a real-world experiment. Just as Germany was broken into two pieces by political ideology (and then later recombined with the East doing much worse than the west) we will now be able to measure what will happen to various countries who are attempting to go-it-alone.

- update: much of the international financial district of London (clearing houses, etc) has moved to Dublin, Amsterdam, Paris and Frankfurt.

Thomas Paine and the Promise of America (2005) Harvey Kaye

The

second chapter covers 18th century life in England (which helped forge Paine's intellect) and justifies the purchase of this book. For example, while it was true that all

Englishmen had civil rights, full civil rights were only granted to:

The

second chapter covers 18th century life in England (which helped forge Paine's intellect) and justifies the purchase of this book. For example, while it was true that all

Englishmen had civil rights, full civil rights were only granted to:Men, who owned land, who earned more than £40 per year, who were Anglican.

This meant that a wealthy upper class had more rights than members of the lower classes, and god help you if you were up against one of them in a court of law. Life in 18th century America was not much different where you only needed to be a White Man of property.

Colossus: The Rise and Fall of the American Empire (2004) Niall Ferguson

Is America an empire? Certainly not, according to the USA government. Despite the conquest of two sovereign states in as many years, despite the presence of more than 750 military installations in two thirds of the world's countries and despite his stated intention "to extend the benefits of freedom...to every corner of the world," George W. Bush maintains that "America has never been an empire.""We don't seek empires," insists Defense Secretary Rumsfeld. "We're not imperialistic."

Nonsense, says Niall Ferguson. In Colossus he argues that in both military and economic terms America is nothing less than the most powerful empire the world has ever seen. Just like the British Empire a century ago, the United States aspires to globalize free markets, the rule of law, and representative government. In theory it’s a good project, says Ferguson. Yet Americans shy away from the long-term commitments of manpower and money that are indispensable if rogue regimes and failed states really are to be changed for the better. Ours, he argues, is an empire with an attention deficit disorder, imposing ever more unrealistic timescales on its overseas interventions. Worse, it’s an empire in denial—a hyperpower that simply refuses to admit the scale of its global responsibilities. And the negative consequences will be felt at home as well as abroad. In an alarmingly persuasive final chapter Ferguson warns that this chronic myopia also applies to our domestic responsibilities. When overstretch comes, he warns, it will come from within—and it will reveal that more than just the feet of the American colossus is made of clay.

Other Literary Diversions

Asimov's Guide to the Bible (1982) Isaac Asimov (PhD Biochemistry)

highly recommended for Judeo-Christians wishing to learn more about life in ancient times- I just (2016.11.xx) purchased this all-in-one book through http://www.bookfinder.com

- I have always wanted to read this book but internet tools have now enabled me to purchase a hard copy

- It weighs-in at 1295 pages and consists of two other previously-published books:

- Asimov's Guide to the Bible: The Old Testament (1967)

- Asimov's Guide to the Bible: The New Testament (1971)

- Asimov apparently researched this book using various sources like:

- The Authorized Version (a.k.a. The King James Bible)

- The Revised Standard Version

- Saint Joseph "New Catholic Edition"

- The Jerusalem Bible

- The Holy Scriptures according to the Masoretic text

- Anchor Bible

- A New Standard Bible Dictionary (Third Revised Edition)

- The Abingdon Bible Commentary

- Dictionary of the Bible

- I wished I would have read these books during the time of my mandatory (as far as my parents were concerned) 3-years religious study which culminated in my Christian

Confirmation at age 13. Why? This is easier to read than the Bible since it includes much historical commentary about the people and cultures of the time (secular

history is tied with biblical events -AND- there are a lot of maps)

- most references to Ethiopia actually mean Nubia