Hacker Perspective: Science Fiction (mostly Asimov + Clarke)

There are no cookies, no advertisements of any kind, and nothing for sale.

(A few noteworthy) Sci-fi Quotes

Forward to: "The Collected Stories of Arthur C. Clarke"

Two 'Hard Sci-fi' Writers (Asimov + Clarke)

What is hard science-fiction? Read this short Wikipedia article

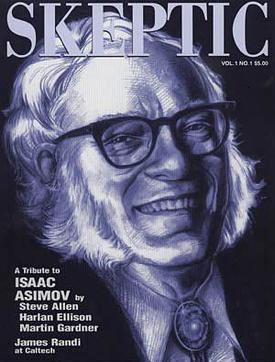

Isaac Asimov (PhD Biochemistry - not an honorary degree)

From

the dust jacket of "The Caves of Steel"

From

the dust jacket of "The Caves of Steel"Doubleday 1954 hardcover edition

For a long time the author has led a double life: one as one of the masters of the fast, terse, often humorous galactic melodramas, and as a biochemist and teacher at the Boston University School of Medicine, where he is engaged in cancer research. Mr. Asimov says: "Science Fiction invades most of the facets of my life, even my serious research. At my final examination for a doctorate in biochemistry (with seven professors asking profound and embarrassing questions) the last question concerned one of the incidents in one of my science-fiction stories. I got my degree." Mr. Asimov also says he is better known for such stories as Pebble in the Sky, The Stars, Like Dust and The Currents of Space in the science fiction world (which takes science fiction very seriously) than he is ever likely to be for his cancer research.

TODAY'S (1954) FICTION - TOMORROW'S FACTS

LIFE Magazine says there are more than TWO MILLION science fiction fans in this country. From all corners of the nation comes the resounding proof that science fiction has established itself as an exciting and imaginative NEW FORM OF LITERATURE that is attracting literally tens of thousands of new readers every year! Why? Because no other form of fiction can provide you with such thrilling and unprecedented adventures! No other form of fiction can take you on an eerie trip to Mars ... amaze you with a journey into the year 3000 A.D. ... or sweep you into the fabulous realms of unexplored Space! Yes, it's no wonder that this exciting new form of imaginative literature has captivated the largest group of fascinated new readers in the United States today!

Introduction to chapter 4 (The 3-D Molecule)

In the days when I was actively teaching, full time, at a medical school, there was always the psychological difficulty of facing a sullen audience. The students had come to school to study medicine. They wanted white coats, a stethoscope, a tongue depressor, and a prescription pad. Instead, they found that for the first two years (at least, as it was in the days when I was actively teaching) they were subjected to the "basic sciences." That meant they had to listen to lectures very much in the style of those they had suffered through in college. Some of those basic sciences had, at least, a clear connection with what they recognized as the doctor business, especially anatomy, where they had all the fun of slicing up cadavers. Of all the basic sciences, though, the one that seemed least immediately "relevant," farthest removed from the game of doctor-and-patient, most abstract, most collegiate, and most saturated with despised Ph.D.'s as professors was biochemistry. —And, of course, it was biochemistry that I taught. I tried various means of counteracting the natural contempt of medical student for biochemistry. The device which worked best (or, at least, gave me most pleasure) was to launch into a spirited account of "the greatest single discovery in all the history of medicine"—that is, the germ theory of disease. I can get very dramatic when pushed, and I would build up the discovery and its consequences to the loftiest possible pinnacle. And then I would say, "But, of course, as you probably all take for granted, no mere physician could so fundamentally revolutionize medicine. The discoverer was Louis Pasteur, Ph.D., a biochemist."

Doubleday 1985 hardcover edition

Isaac Asimov’s ROBOTS AND EMPIRE heralds a major new landmark in the great Asimovian galaxy of science fiction. For it not only presents the thrilling sequel to the best-selling The Robots of Dawn, but also ingeniously interweaves all three of Asimov’s classic series: Robot, Foundation, and Empire. This is the work Asimov fans have been waiting for—an electrifying tale of interstellar intrigue and adventure that sets a new standard for the realm of SF literature.

Two hundred years have passed since The Robots of Dawn and Elijah Baley, the beloved hero of the Earthpeople, is dead. The future of the Universe is at a crossroads. Though the forces of the sinister Spacers are weakened, Dr. Kelden Amadiro has never forgotten—or forgiven—his humiliating defeat at the hands of Elijah. Now, with vengeance burning in his heart, he is more determined than ever to bring about the total annihilation of the planet Earth.

But Amadiro has not counted on the equally determined Lady Gladia. Devoted to Elijah Baley, the Auroran beauty has taken up the legacy of her fallen lover, vowing to stop the Spacers at any cost. With her two robot companions, Daneel and Giskard, she prepares to set into motion a daring and dangerous plan…a plan whose success—or failure—will forever seal the fate of Earth and all who live there.

Culminating in a stunning surprise climax, ROBOTS AND EMPIRE is singular science fiction that excites the mind and stimulates the imagination. It is Isaac Asimov at his triumphant best, proving him, once again, the true Master of the genre.

From the introduction to "Foundation and Earth"

Doubleday 1986 hardcover edition

On August 1, 1941, when I was a lad of twenty-one, I was a graduate student in chemistry at Columbia University and had been writing science fiction professionally for three years. I was hastening to see John Campbell, editor of Astounding, to whom I had sold five stories by then. I was anxious to tell him of a new idea I had for a science fiction story.

It was to write a historical novel of the future; to tell the story of the fall of the Galactic Empire. My enthusiasm must have been catching, for Campbell grew as excited as I was. He didn't want me to write a single story. He wanted a series of stories, in which the full history of of the thousand years of turmoil between the First Galactic Empire and the rise of the Second Galactic Empire was to be outlined. It would all be illuminated by the science of psychohistory that Campbell and I thrashed out between us.

The first story appeared in the May 1942 Astounding and the second story appeared in the June 1942 issue. They were at once popular and Campbell saw to it that I wrote six more stories before the end of the decade. The stories grew longer too. The first one was only twelve thousand words long. Two of the last three stories were fifty thousand words apiece.

By the time the decade was over, I had grown tired of the series, dropped it, and went on to other things. By then, however, various publishing houses were beginning to put out hardcover science fiction books. One such house was a small semiprofessional firm, Gnome Press. They published my Foundation Series in three volumes: Foundation (1951); Foundation and Empire (1952); and Second Foundation (1953). The three books together came to be known as The Foundation Trilogy.

The books did not do very well, for Gnome Press did not have the capital with which to advertise and promote them. I got neither statements nor royalties from them.

In early 1961, my then-editor at Doubleday, Timothy Seldes, told me he had received a request from a foreign publisher to reprint the Foundation books. Since they were not Doubleday books, he passed the request on to me. I shrugged my shoulders. "Not interested, Tim. I don't get royalties on those books"

Seldes was horrified, and instantly set about getting the rights to the books from Gnome Press (which was, by that time, moribund), and in August of that year, the books (along with "I, Robot") became Doubleday property.

From that moment on, the Foundation series took off and began to earn increasing royalties. Doubleday published the Trilogy in a single volume and distributed them through the Science Fiction Book Club. Because of that the Foundation series became enormously well known.

In the 1966 World Science Fiction Convention, held in Cleveland, the fans were asked to vote on a category of "The Best All-Time Series". It was the first time (and, so far, the last) the category had been included in the nominations for the Hugo Award. The Foundation Trilogy won the award, which further added to the popularity of the series.

Increasingly, fans kept asking me to continue the series. I was polite but I kept refusing. Still, it fascinated me that people who had not been born when the series was begun had managed to become caught up in it.

Doubleday, however, took the demands far more seriously that I did. They had humored me for twenty years but as demands kept growing in intensity and number, they finally lost patience. In 1981, they told me that I simply had to write another Foundation novel and, in order to sugar-coat the demand, offered me a contract at ten times my usual advance.

Nervously, I agreed. It had been thirty-two years since I had written a Foundation story and now I was instructed to write one 140,000 words long, twice that of any earlier volumes and nearly three times as long as any previous individual story. I re-read The Foundation Trilogy and, taking a deep breath, dived into the task.

The fourth book of the series, Foundation's Edge, was published in October 1982, and then a very strange thing happened. It appeared in the New York Times bestseller list at once. In fact, it stayed one that list for twenty-five weeks, much to my utter astonishment. Nothing like that had ever happened to me.

Doubleday at once signed me up to do additional novels and I wrote two that were part of another series, The Robot Novels. - And then it was time to return to the Foundation.

So I wrote Foundation and Earth, which begins at the very moment that Foundation's Edge ends, and that is the book you now hold. It might help if you glanced over Foundation's Edge just to refresh your memory, but you don't have to, Foundation and Earth stands by itself. I hope you enjoy it.

New York City, 1986

Okay so it was only a few paragraphs from a just-delivered used book originally published in 1988, but I was "in the zone" so took it seriously because it reminded me of the posthumous messages sent by Hari Seldon to all of humanity, via the Time Vault, in Asimov's Foundation Trilogy. Sci-fi fans should read this message too because Asimov's Favorite Fifteen are the basis for a provocative humanistic-robotic philosophy so awe-inspiring that I could, if I so desired, create a religion based upon it (although I would not because Asimov would not have approved). Although half of Asimov's stories were written in the 1940s and 1950s, they do not seem anachronistic in any way. In fact, they seem to have been written last week.

Doubleday 1988 hardcover edition © 1988 by Nightfall Inc.

When I wrote Foundation, which appeared in the May 1942 issue of Astounding Science Fiction, I had no idea I had begun a series of stories that would eventually grow into six volumes and a total of 650,000 words (so far). Nor did I have any idea that it would be unified with my series of short stories and novels involving robots and my novels involving the Galactic Empire for a grand total (so far) of fourteen volumes and a total of about 1,450,000 words.

You will see, if you study the publication dates of these books, that there was a twenty-five-year hiatus between 1957 and 1982, during which I did not add to this series. This is not because I had stopped writing. Indeed, I wrote full-speed throughout the quarter century, but I wrote other things. That I returned to the series in 1982 was not my own notion but was the result of a combination of pressures from readers and publishers that eventually became overwhelming.

In any case, the situation has become sufficiently complicated for me to feel that the readers might welcome a kind of guide to the series, since they were not written in the order in which (perhaps) they should be read. The fourteen books, all published by Doubleday, offer a kind of history of the future, which is, perhaps, not completely consistent, since I did not plan consistency to begin with. The chronological order of the books, in terms of future history (and not of publication date), is as follows:

Syllabus reading order as suggested by Isaac Asimov:click here for a smaller list to copy-paste

| B o o k |

Title | G r o u p |

Asimov's Comments (Neil's comments in RED) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | The End of Eternity (1955) | 0 | One hardcore Asimov fan told me that this book was listed before all the others in a recommended list published in Asimov's Science Fiction Magazine |

| 1 | I, Robot (1950) | 1 | A collection of nine short stories presented as the memoirs of robot psychologist Dr. Susan Calvin (an employee of U.S. Robots and Mechanical Men

Corporation).

|

| The Complete Robot (1982) | A collection of thirty-one robot short stories published between 1940 and 1976 and includes every story in my earlier collection I, Robot

(1950). Only one robot short story has been written since this collection appeared. That is Robot Dreams, which has not yet appeared in any Doubleday collection. |

||

| 2 | Caves of Steel (1954) | 2 | My first robot novel. [Detective Elijah Baley meets R. Daneel Olivaw ] |

| 3 | The Naked Sun (1957) | 2 | My second robot novel. Solaria is a planet where the robots outnumber humans 10,000 to one. |

| 4 | The Robots of Dawn (1983) | 2 | My third robot novel. Aurora is a planet where the human population is limited to 200 million. |

| 5 | Robots and Empire (1985) | 2 | My fourth robot novel. This title comes from a conversation between two robots (page 66) (1) Daneel develops The Zeroth Law (begins on page 192) (2) Giskard develops the beginnings psychohistory (page 186) |

| 6 | The Currents of Space (1952) | 3 | This is the first of my [Galactic] Empire novels. |

| 7 | The Stars, Like Dust (1951) | 3 | The second [Galactic] Empire novel. |

| 8 | Pebble in the Sky (1950) | 3 | The third [Galactic] Empire novel and first novel. |

| 9 | Prelude to Foundation (1988) | 4 | This is the first Foundation novel. |

| 10 | Forward the Foundation (1993) | 4 | This is the second Foundation novel. [ this title was not in Asimov's original list; Fourteen books become Fifteen ] |

| 11 | Foundation (1951) | 5 | The is the third Foundation novel, but is more commonly known as the first book of the Foundation Trilogy.

Actually, it began as a collection of four short stories, originally published between 1942 and 1944, plus an introductory section written for the book in

1949. Read: the story behind The Foundation |

| 12 | Foundation and Empire (1952) | 5 | This is the fourth Foundation novel, but is more commonly known as the second book of the Foundation Trilogy. It originated from of two short stories, originally published in 1945. |

| 13 | Second Foundation (1953) | 5 | This is the fifth Foundation novel, but is more commonly known as the third book of the Foundation Trilogy. It originated from two short stories, originally published in 1948 and 1949. |

| 14 | Foundation's Edge (1982) | 4 | This is the sixth Foundation novel. |

| 15 | Foundation and Earth (1986) | 4 | This is the seventh Foundation novel. [ Asimov's list shows a publishing date of 1983 but this is a typo ] |

Will I add additional books to the series? I might. There is room for a book between Robots and Empire and The Currents of Space, and between Prelude to Foundation and Foundation, and of course between others as well. And then I can follow Foundation and Earth with with additional volumes -- as many as I like. Naturally, there's got to be some limit, for I don't expect to to live forever, but I do intend to hang on as long as possible.

General Notes:

- No book was ever published (by Asimov) to fill the gap between Robots and Empire and The Currents of Space

- Asimov died at age 72 in 1992

- Forward the Foundation (published posthumously in 1993) fills the gap between Prelude to Foundation and Foundation.

So, what was colloquially known as Asimov's Favorite Fourteen now becomes Asimov's Favorite Fifteen. - With all due respect to the title of the 1965 movie, Asimov's Favorite 15 comprise "The Greatest Story Every Told"

Column-3 (Group) Notes:

- Even though this book {I, Robot} was originally published in 1950, the pre-1950 stories contained within seem to stand the test of time. This

might have something to do with the fact that Asimov usually glosses over technological details while concentrating more on the human side of things. Remembering

that these stories were written during the age of vacuum tubes which predates solid state electronics (transistors and integrated circuits). Asimov never mentions

these components but does use the phrase "Positronic Brain" as a literary device for "unknown technology". One "possibly" dated phrase is "robot psychologist" to

mean "computer programmer". However, the field of Artificial Intelligence (AI) programming is now becoming so complex that "robot psychology" may become a

programming discipline.

- The story Robot Dreams did appear in a robot compilation published by Byron Press in 1986 titled Robot Dreams. A second

robot compilation was published by Byron Press in 1990 titled Robot Visions.

- The story Robot Dreams did appear in a robot compilation published by Byron Press in 1986 titled Robot Dreams. A second

robot compilation was published by Byron Press in 1990 titled Robot Visions.

- Books 2, 3, and 4 (but not 5) were republished in 1988 under the title The Robot Novels

- Book 5 (Robots and Empire) is sometimes jokingly referred to as the fourth book of the Robot Trilogy

- Book 5 (Robots and Empire) is sometimes jokingly referred to as the fourth book of the Robot Trilogy

- Books 6-8 are part of Asimov's Galactic Empire series. Asimov thought that these books were not very good (as far as the Robot-to-Foundation

story line is concerned). He once stated "You can skip these books and still have a very enjoyable read [of the other 12]"

- Primarily due to the book clubs of the 1950s and 1960s, there once was a time when Asimov was better known for these three books than he was for the Foundation Trilogy

- Book 8 (Pebble in the Sky) was republished in hardcover on January 2008 and I enjoyed it immensely.

- Book 7 (The Stars, Like Dust) was republished in hardcover on December 2008 and I enjoyed it as well.

- Book 6 (The Currents of Space) was republished in hardcover on April 2009 and think it was worth every penny.

- Book 10 (Forward the Foundation) was not in Asimov's original list because he had not yet written it. This means that books 11-15 reflect new

numbers. Forward the Foundation was Asimov's final book. Click here for suppressed information about Asimov's

death in 1992 at the age of 72.

- Books 11-13 are known by the public-at-large as The Foundation Trilogy. Even still, for maximum enjoyment you should read books 9-15 in order.

Since some well known Robots pop up here, you should read books 1-5 (or 1-8) first.

- It is unfortunate that we cannot able to travel back in time to convince Asimov to get 45 minutes of daily exercise so he could avoid the triple

bypass surgery responsible for infecting his blood with a deadly virus. I cannot imagine this collection without Forward the Foundation and

now can only wonder about what he had in mind for these other insertion points. Generally speaking, Asimov fans have been very critical about the work done by other

authors commissioned by Asimov's estate.

- If you are a hard sci-fi fan like me then every one of these 15 books are worth reading today. They seem to stand the test of time and do not seem dated in any way. Locate rare and out-of-print books: www.bookfinder.com

Readers familiar with the Sherlock Holmes stories know that Doctor Watson referred to himself as Holmes' biographer. People who have immersed themselves in those stories have come to the realization that Arthur Conon Doyle was, in effect, Watson. The fact that Doyle was a real-world medical doctor is just icing on the cake. Now the same claim can be made about the relationship with author "Isaac Asimov" and one of his fictional characters, Hari Seldon

It has not escaped my attention that "stumbling upon Asimov's suggested reading order in an original imprint from 1988" is very much like "receiving a posthumous message from Hari Seldon". Yes, Asimov still speaks to humanity today but I am certain he wouldn't want you to turn his humanist-robotic philosophies into a religion even though you could.

As a computer technologist, I find it amusing that most people today confuse A.I. (artificial intelligence) with artificial consciousness. While A.I. has brought fully autonomous vehicles close to general use, a vehicle that accidentally causes a crash will not be able to be interviewed by an investigating police officer, or dragged into court to give testimony. It appears to me that Asimov already broached these issues in his stories which are dominated by robots. Artificial intelligence is everywhere (Detective Baily talks about "logic vs reason") but only these two robots seemed to possess artificial consciousness: Together, they co-develop the zeroth law of robotics which is used (over the course of 15 books) to save humanity from itself. Or did they? Here is an excerpt from page 116 of The Naked Sun (1959 imprint of a 1957 story):

Baily - It is as much my job to prevent harm to man-kind as a whole as yours is to prevent harm to a man as an individual. Do you see?

Daneel - I do not, Partner Elijah (but he eventually would)

- The End of Eternity

- I, Robot

- Caves of Steel

- The Naked Sun

- The Robots of Dawn

- Robots and Empire

- The Currents of Space

- The Stars, Like Dust

- Pebble in the Sky

- Prelude to Foundation

- Forward the Foundation

- Foundation

- Foundation and Empire

- Second Foundation

- Foundation's Edge

- Foundation and Earth

Resources

- Local Links

- My own reviews of Asimov's-15 were deleted on 2016.12.25 because Wikipedia does a better job (but if you really want to read them then click here)

- See what Asimov had to say about Protein Folding in 1990.

- Skip to my last "Isaac Asimov" paragraph below to learn about Isaac Asimov's strange and tragic death in 1992.

- Wikipedia Links

- It is my belief that www.wikipedia.org is humanity's first real attempt at an Encyclopedia Galactica (although it was not implemented as Asimov envisioned in his Foundation Trilogy)

- Isaac Asimov

- Foundation Trilogy

- Robot Series

- Galactic Empire Series

- Other Links

Some Useful Multimedia Links:

- Isaac Asimov on Bill Moyers World of Ideas

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Uj7IXIAReMM

-

www.pbs.org/moyers/journal/blog/2008/03/bill_moyers_rewind_isaac_asimo_1.html

In 1988, Bill Moyers interviewed author Isaac Asimov for WORLD OF IDEAS. Incredibly prolific in various genres beyond the science fiction for which he was best known, Asimov wrote well over 400 books on topics ranging from sci-fi to the Bible before his death in 1992. In one thread of his wide-ranging interview, Asimov shared his thoughts on overpopulation:Bill Moyers: "What happens to the idea of the dignity of the human species if this population growth continues at its present rate?"

Isaac Asimov: "It will be completely destroyed. I like to use what I call my bathroom metaphor: If two people live in an apartment, and there are two bathrooms, then both have freedom of the bathroom. You can go to the bathroom anytime you want, stay as long as you want, for whatever you need. And everyone believes in Freedom of the Bathroom; It should be right there in the Constitution. But if you have twenty people in the apartment and two bathrooms, then no matter how much every person believes in Freedom of the Bathroom, there's no such thing. You have to set up times for each person, you have to bang on the door, 'Aren't you through yet?' And so on." Right now most of the world is living under appalling conditions. We can't possibly improve the conditions of everyone. We can't raise the entire world to the average standard of living in the United States because we don't have the resources and the ability to distribute well enough for that. So right now as it is, we have condemned most of the world to a miserable, starvation level of existence. And it will just get worse as the population continues to go up... Democracy cannot survive overpopulation. Human dignity cannot survive it. Convenience and decency cannot survive it. As you put more and more people onto the world, the value of life not only declines, it disappears. It doesn't matter if someone dies. The more people there are, the less one individual matters."

- Isaac Asimov speaks

- part -1: Threats to Humanity

www.youtube.com/watch?v=LO0sCs8jI4k - part-2: The Answer for Humanity

www.youtube.com/watch?v=TpHPQCnHHl4

- part -1: Threats to Humanity

Sad Information About the Death of Isaac Asimov

In 2002-08-10 it was revealed by Dr. Asimov's widow, Dr. Janet Jeppson Asimov, in the new biography It's Been a Good Life (my review below), that his death was in fact due to AIDS. In 1983 he had triple bypass surgery and received blood transfusions containing HIV. (Ironic that the city he loved was the cause of his death; doubtless nowhere else in the United States had a higher incidence of HIV in the blood supply than New York at that time) As Dr. Jeppson Asimov states, after his triple bypass "the next day he had a high fever... only years later, in hindsight, did we realize that the post transfusion HIV infection had taken hold." In the mid-Eighties Dr. Jeppson Asimov noted that her husband had some AIDS symptoms and brought them to the attention of his internist and cardiologist, who pooh-poohed and refused to test him. He was finally tested in February of 1990, prior to further surgery, when he presented HIV-positive with his T-cells half the normal level. The astonishing fact of Dr. Asimov's AIDS was kept secret at the advice of his physicians - they apparently strong-armed him in his sickbed with the threat that his wife would be shunned as a suspected PWA (Person With AIDS) as well. The secret was kept not till after Dr. Asimov's death in 1992, but until after the death of his physicians (see Dr. Jeppson Asimov's letter to Locus magazine).So there you have it. The whole world has been deprived of probably another dozen books by Isaac Asimov. I wished we could have convinced him to diet and exercise so he could have avoided both "the triple-bypass surgery" as well as "the associated blood transfusions". Since he was smarter than us we can only ask ourselves "why did this PhD not engage in preventative measures to prevent this situation?"

Some time after creating my own online review of Isaac Asimov's books in 2004, I discovered a much better collection of reviews at Wikipedia.

Sidelined content was moved here to reduce the size of this page.

Foundation on AppleTV

I like this TV adaptation. But unlike Dune (1984 film) and Dune (2021 film) where the viewer can get a fairly good idea what is happening ("story-wise") without reading Frank Herbert's first book, I fear that some Foundation viewers...- may not get through Foundation season-1 episode-1 unless they have read Asimov's books, or are familiar with the items in this: non-spoiler general outline (yellow block below)

- may get lost by the second or third episode where some characters quickly age, but not do not

- The AppleTV version is a slightly different adaptation with some of the male characters in the original version now being represented by female characters (believe me when I say that these changes work)

- This story takes place around the year 12,000 and starts with this overview: https://asimov.fandom.com/wiki/Foundation

- Gaal Dornack is a mathematician born on Synnax in the 13th millenium GE. In 12,067. Shortly after being awarded a Doctorate in mathematics (for solving the Abraxas Conjecture), she is invited to Trantor by Hari Seldon to join the psychohistory project.

- Hari Seldon is a mathematician born in the 11,988th year of the Galatica Era and died 12069. He invented a new branch of mathematics called psychohistory

- psychohistory is a branch of mathematics where statistics, history and sociology are combined in computer-based models to predict humanity's general overall future

- Hari Seldon's analysis of psychohistory indicates a possible 30,000 year dark age is about to unfold, but this might be reduced to just 1,000 years if certain

precautions are taken like

- creating an Encyclopedia Galactica to preserve current knowledge (so rediscovery would not required after the collapse).

- creating a Time Vault

- When emperor Cleon XIII hears of the impending dark age, Seldon and Dornak are banished to the planet Trantor which is on the other side of the galaxy

- Near the end of the second season, Demerzel (majordomo and sometimes imperial courtesan) states that she is 18,000 years old, and is the last of the humaniform robots. I wonder if she is related in anyway related to R. Daneel Oliva?

Continuation: Arthur C Clarke

Back to Home

Back to HomeNeil Rieck

Waterloo, Ontario, Canada.